By Ousman Saidykhan

December 2017, a wind of change was sweeping across Gambia. A long-standing dictator, Yahya Jammeh, lost to an opposition leader, Adama Barrow. Jammeh enjoyed a tight grip on the Gambian military, a large chunk of which was said to be loyal to him, prompting a regional military intervention after he refused to step down claiming electoral fraud.

The allegations Jammeh used the military in human rights abuse, some of whom are reportedly from Casamance, led to calls for reforms of security institutions. Caught up in the hunt for Jammeh loyalists is a 40-year-old native of Kabakel, Omar Sarjo. Or for the Gambia government, a native of Karechak, a little-known village in Casamance, south of Senegal.

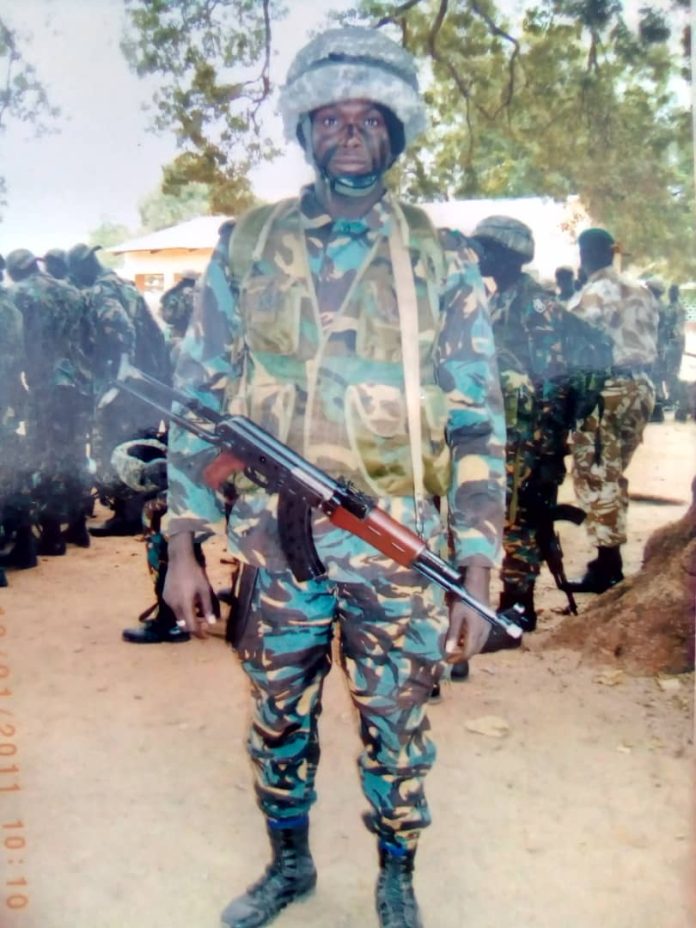

It was a windy morning on September 16. A 40-year-old Omar Sarjo, father of 3, returned from a cassava farm in Yundum barracks. His cheeks dripped with sweat as he went for a shower. He had an appointment with a reporter. In an earlier life, Omar would have been adorned in a military camouflage with an AK47 rifle dangling on his shoulder. Omar served the Gambian military for 13 years until he was sacked in 2017 for alleged affiliation to the bloodline of Senegalese separatist leader Salif Sadio. He was a corporal.

Now, he lost his job, with it all his entitlements. Omar turned to a 20 by 35 meters land – situated within the army camp in Yundum, just about a stone’s throw from his house— for survival.

“I cultivate cassava…and bananas, and other crops. That is what is helping me. The difficulty there is, as a family man, you can’t just sit. My wife helps too,” said Omar, in a much lower voice, with splatters of tears in his eyes.

How Omar’s nightmare began still has a huge shadow cast over it. The first allegations emerged after the military claimed it conducted an investigation— on a tip-off supplied by an unnamed informant— which confirmed that Omar was Salif Sadio’s son. The investigation report, which the military claimed was classified, was presented before the court but never made public. Three years later, the army conducted another investigation, confirming their initial story was untrue. But then, another allegation emerged that he went into the army using someone’s document.

What happened to Omar is an indictment of the army’s recruitment process, said Alagie Saidy Barrow, a former captain in the US military and the director of research and investigation at the Truth Commission that investigated the human rights violations of the former president Yahya Jammeh. Barrow said the military recruitment process should have provided safeguards which makes it impossible for someone to make through with fake documents. “Who was at the door when he (Omar) came in? What happened to that person? We don’t know, and that is just as important to know,” added Barrow.

At a date he could not remember, Omar was returning to his away-guard duty in Sibanor, Foni, when he received a call from his wife informing him that his superiors in Banjul claimed he was a son of the Senegalese separatist leader. It was 2017, at the dawn of the presidency of the president who had deep-seated suspicion of the military’s loyalty to Jammeh. Any association with Casamance’s rebel leader Sadio, with whom Jammeh reportedly had a strong tie, was not to be taken lightly. Omar knew his 13-year career just ended for being the son of a man he had never met.

“I felt so bad. It is an allegation that destroyed my life,” said Omar.

Price of being in the shadow of a rebel leader

Senegal has fought rebellion in its southern region since 1982. The rebels have since been blamed for thousands of deaths. While the insurgents have yet to turn their guns on Gambians, the effect of their conflict with Senegalese forces often spills over to the Gambian side. More recently, In January 2022, thousands of Gambians were displaced in Foni. Four Senegalese soldiers were killed after a clash with a rebel faction loyal to Salif Sadio.

Omar’s dismissal was followed by a highly publicized ‘affiliation’ to the bloodline of the rebel leader blamed for several deaths. The nightmare began.

“You know who Salifu Sarjo is. If you’re accused of being his son, people would assume you will be like him,” said Omar. “People discriminate against me everywhere.”

The stigma cost him his job, as it turned out, killed any prospect of a new job. All the vacancies he applied for since 2017, most of which are security jobs, only ended up appearing before an interview panel.

“… As soon as they see the name Omar Sarjo from Kabakel, they remember I’m the one accused of being Salifu Sadio’s son.” He leaves and no call later.

But not only does Omar have to live in Gambia with stigma, he can’t leave the country either. After he was sacked from the military, a brother of his living in the United Kingdom reached out. He offered to help him to travel to Dubai, in the United Arab Emirates. After a successful negotiation with the travel agency, Omar was required to pay a non refundable fee of D180, 000.

Instead of the renewal he had hoped for, the immigration seized Omar’s passport on charges he was not a Gambian. “… I could have used that D180,000 on something else. I have a piece of land. I could have fenced it and built it little by little,” said Omar.

But just as the opportunity to travel to Dubai slipped through his fingers, so began a legal battle against him.

For almost five years— from 2018 to 2022— Omar fought to clear his name until the Magistrate Court in Banjul acquitted and discharged him on charges of attempting to acquire a Gambian passport illegally.

After the court’s decision, the lawyer—Ababucarr A.M.O Badjie—would ensure that he renewed his passport and national ID card in April 2022.

Wheel of life spins, regardless

In 2017, the take-home pay of a corporal in the Gambian army was D2468. There is little, if any, to save, which means Omar can’t afford a rest or a day out of a job. “…It is difficult, really. Being a man who is not working but needs to feed a family, and the children need to go to school too. It is hard.”

The “little” savings Omar made before his dismissal were what he withdrew “little by little” to buy bags of rice and foodstuffs for their daily survival and school materials for his children.

At the time he was terminated, he had two kids. Both are girls and go to school. The third child was born when he was already dismissed and struggling. Each of the two school-going girls goes with D25 for “lunch” every day of the week.

That is equal to D250 a week, D4,500 per term, and D13,500 in a school year. Out of job, and ostracised, Omar turned to his farm to ensure the children remain in school and nourished.

“… I really face huge difficulties – huge ones. And the Army— an institution I served for 13— is responsible,” Omar said.

Power of men… and of law

The consequences of the state’s actions had a different effect on Omar. He was out of work, socially ostracised, and without vital national documents.

His lawyer took a fight to the army to get his job back. In a case filed in January 2021 at the High Court, Badjie sought the court to declare Omar’s dismissal illegal.

In November 2021, the court sided with Omar, declaring that the army acted wrongly. The army never appealed the judgment but failed to reinstate Omar.

Though the defence ministry received the legal advice on July 9, 2024, the minister, Sering Momodou Njie, told lawmakers a day later they were yet to hear from the justice ministry.

In its two-page legal advice to the Ministry of Defense, the Ministry of Justice claimed the judgment that established the illegality of the army’s decision to sack Omar fell short of asking for his reinstatement. The legal advice arrived at the army chief’s desk on August 8, a month after the Ministry of Defense received it.

“…Mr Omar Sarjo cannot be reinstated into the Gambia Armed Forces because the judgement is not executory,” said the justice ministry.

In another appearance before the parliament on September 18, 2024, the defence minister told lawmakers of their intent to meet Omar during the week. Until the beginning of October, Omar confirmed he had not met with the Ministry or the army.

However, does the Ministry of Defense require legal advice to take action on Omar’s case? A constitutional lawyer Lamin J Darboe does not think so. Darboe likened the case to that of Ya Kumba Jaiteh, where the Supreme Court held that the decision of the President to sack her as a nominated lawmaker was unconstitutional.

“The declarations in both cases are self-executory and the public bodies concerned must simply rectify their erroneous decisions,” said Counsel J Darboe. “Mr. Sarjo was at no point dismissed and he is owed all his entitlements and must be reinstated.”

To reinstate or not, the debate between Omar’s lawyer and the Ministry of Defense rages. And while there is enough time for conversation, life continues so does the daily expenses Omar has had to break a back to meet. We have reached out to the Minister of Defense, Hon Njie, and his permanent Rohey Bittaye, to inquire about their intended meeting with Omar, but we could not get a comment until the time of this publication. We have also sent questions to the spokesperson of the Gambia Armed Forces, Col. Lamin K. Sanyang, but we have not received a reply until the publication.

……………….

This story is produced with support from the PRJ investigative reporting fellowship, with funding from USG through USAID, and implemented by Freedom House. The content of this report does not in any way reflect the views of the US government, USAID, or Freedom House. It is the sole responsibility of the author and publisher.