By Alieu Ceesay

In a scene reminiscent of authoritarian crackdowns, the serene corridors of the National Audit Office (NAO) in Kanifing descended into chaos on Monday morning as officers from Kairaba Police Station stormed the premises, forcibly removing Director Auditor Modou Ceesay from his third-floor office. The dramatic eviction, witnessed by tearful staff and journalists, has ignited a firestorm of condemnation, with Ceesay announcing plans to sue the government for what he and rights advocates call an unconstitutional assault on institutional independence.

The incident unfolded against a backdrop of political maneuvering that began just five days earlier. On September 10, President Adama Barrow reshuffled his cabinet, appointing Ceesay, who has served as Auditor General since November 2022, as Minister of Trade, Industry, Regional Integration, and Employment.

The move replaced the incumbent minister, Baboucar Ousmaila Joof, who was reassigned to Defence. The State House claimed Ceesay initially accepted the offer during a meeting with the president, even exchanging hugs and smiles as he received his appointment letter.

However, Ceesay vehemently denied this, insisting he never consented and formally rejected the position on September 11 in a letter to the Presidency, citing his constitutional duty to uphold public sector auditing.

Undeterred, the government proceeded with the transition, naming Cherno Amadou Sowe, head of the Directorate of Internal Audit at the Ministry of Finance, as Ceesay’s successor.

Ceesay, a seasoned finance and audit professional with over a decade of experience in public sector governance, risk management, and internal controls, viewed the maneuver as a ploy to sideline his office’s probing reports on corruption and financial mismanagement.

During his tenure, Ceesay had championed reforms, including the implementation of the SAI-Enhancement Audit Tool (GamSEAT) to automate audits and enhance transparency, earning praise for bolstering The Gambia’s governance ratings.

What should have been a routine Monday turned extraordinary at the NAO headquarters. Staff, showing unprecedented solidarity, arrived as early as 6 a.m. – hours before the typical 8 a.m. start for Gambian civil servants – lining the entrance to welcome their leader back to work. “It was like a family reunion,” one anonymous auditor recounted, her voice cracking. “We wanted to show him we’re with him, no matter what.”

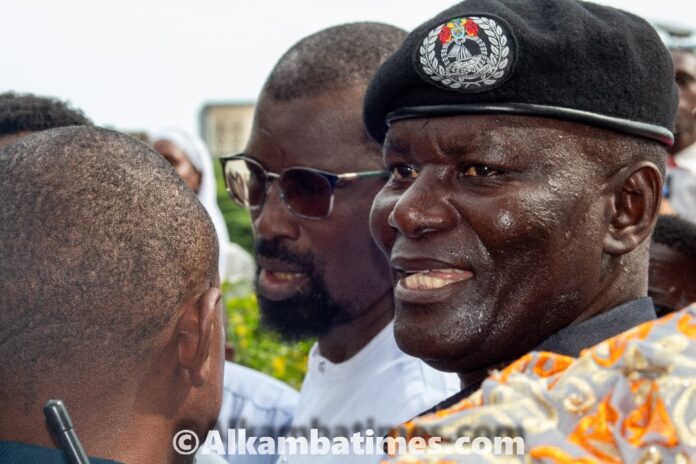

Ceesay, undaunted, arrived shortly after, addressing a throng of staff and reporters in the lobby. “I was informed this morning that there were officials from Kairaba police station asking for me,” he said calmly, his tone measured yet resolute. “But I am here to just do my work. That’s why I came as usual – to fulfill what I’ve been assigned to do.”

Responding to speculation about his removal, he added, “We’ll try to follow due process in whatever we do and comport ourselves in accordance with the dictates of a professional. We can’t speculate much about what will happen.”

He categorically refuted government claims of acceptance: “I did not accept the ministerial position prior to declining it.” Emphasizing the legal safeguards, Ceesay invoked the 1997 Constitution and the National Audit Office Act of 2015, which stipulate that the Auditor General “shall not be subject to the direction or control of any person or authority” and can only be removed for stated misbehavior or incompetence through a rigorous parliamentary process.

“The procedures for removal are set out very clearly,” he stressed. “When it comes to accountability and good governance, the independence of audit offices is a very important factor in enhancing governance ratings and the credibility of any nation.”

The mood shifted abruptly around 10 a.m. when a contingent of uniformed officers, backed by plainclothes personnel, entered the building. Eyewitnesses described a tense standoff as police demanded Ceesay vacate the premises immediately. “They said he was no longer in charge and had to leave until further notice,” a staffer whispered, wiping away tears. Resistance was futile; officers escorted – or, as some accounts suggest, dragged – Ceesay from his office to a waiting tinted SUV outside. Heart-wrenching scenes unfolded: several female auditors sobbed openly, hugging colleagues in disbelief, while others filmed the ordeal on their phones.

Compounding the humiliation, police seized Ceesay’s official vehicle and cleared his office of personal effects. “It felt like a raid, not a transfer,” one observer noted. The eviction barred Ceesay from re-entering the NAO, effectively suspending his duties without due process.

By midday, Ceesay had regrouped at the chambers of prominent lawyer Lamin J. Darboe, a veteran human rights advocate known for challenging state overreach. Flanked by loyal staff, he emerged to declare his intent to file a lawsuit. “This is a blatant violation of the law,” Ceesay told reporters outside Darboe’s office. “We will seek judicial intervention to reinstate me and affirm the independence of the NAO. The battle ahead will test our commitment to accountability and transparency in the modern world.”

Darboe, echoing his client’s resolve, promised a “robust defense of constitutional principles.” The legal challenge could invoke Sections 3(2) and 14(a) of the 2015 Act, potentially escalating to the Supreme Court. Rights groups were quick to rally: The Edward Francis Small Centre for Rights and Justice (EFSCRJ) labeled the removal “illegal and a direct threat to The Gambia Transparency and Accountability efforts,” demanding immediate reversal

This saga draws uncomfortable parallels to past controversies, such as the 2021 ousting of Central Bank Governor Bakary Jammeh, who contested his ministerial reassignment as unconstitutional before relenting.

As twilight fell over Kanifing, the NAO stood eerily quiet, its doors locked to its former guardian. For Ceesay’s supporters, the eviction isn’t just personal – it’s a litmus test for The Gambia’s democratic credentials. Will the courts uphold the rule of law, or will political expediency prevail? In a nation still healing from dictatorship, the stakes couldn’t be higher. The lawsuit’s filing is expected within days, promising a showdown that could redefine public oversight in West Africa.