By: Alieu Ceesay

Sam Sama returns from the sea. At noon at Bakau beach, the sun was right overhead, as he headed for a crowded landing site packed with fishmongers expecting a good day at sea. As his boat hit the shoreline, everyone jolted from their seats. He had a whole night at sea.

Unfortunately, Sama’s night was not as good. He only had enough for his family. A bad news for women fishmongers who rely on fishermen like him for daily survival.

Sama’s story is one too many.

The fisherfolk have experienced a sharp decline in their catches in the last few years, said Omar Njie, an artisanal fisherman at the Tanji fish landing site. Though this is influenced by many factors, Njie believes a significant contributor is overfishing caused by Senegalese in Gambian waters.

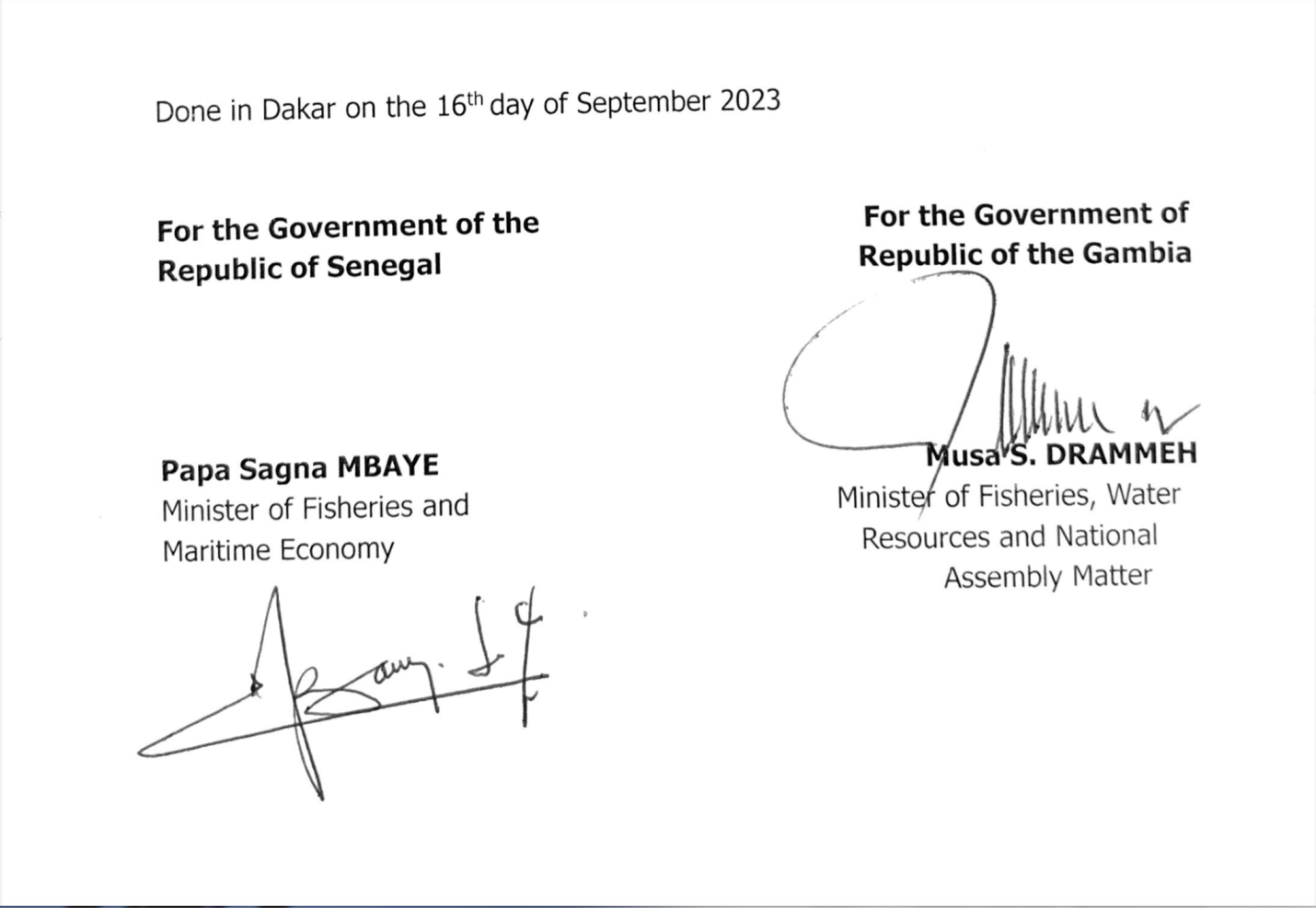

Gambia and Senegal signed a fishing agreement in 2017, renewed in 2023, without the participation of the country’s artisanal fishermen, according to the Gambia National Association of Artisanal Fisheries.

A one-sided deal

Senegal has a far larger pool of artisanal fishers than Gambia. Not only does study establish that the suppliers of the 3 fish meals in the Gambia are Senegalese, there is a significant number of Senegalese fishermen in Gambia. Industry experts and local fishermen said the 4-year fishing agreement renewed in September 2023 gives Senegal far more advantage over Gambia.

The deal allowed Senegal to put 250 boats in the Gambian waters, from 40 horsepower to industrial trawlers. Article one of the agreement allows the fishermen from the French-speaking country to land in Senegal. While the agreement provides a limit of the number of boats allowed to come from Senegal— 250— there is no monitoring mechanism to ensure proper implementation.

The Senegalese fishermen who come to Gambia to fish in the country’s waters and the ones who supply the fish meals during the night fight fishing period are not operating under the agreement, according to media reports.

This appears to be confirmed by the quantity of seaworthy certificates paid to Gambia Maritime Administration by Senegalese boats in 2022 and 2023 which were 282 and 168.

“We are already seeing scarcity of fish in the Gambia,” said a fisheries official who does not want to be named. “The signed agreement is not reciprocal.”

Scarcity forcing price hikes

With article one of the agreement allowing fishermen to land their catch in either country, and Senegalese having the higher buyer power, experts said, this leaves Gambian consumers vulnerable. In July, the fisheries minister Musa S. Drammeh told lawmakers that Senegalese fishermen in Gambia’s waters take their catches home but attribute this to lack of landing ports in the country.

Exporting the fish to Senegal is not the only issue. For Gambian fishermen, far more nets are now competing for fewer resources that continue to deplete.

“We are experiencing a very significant drop in our catch,” said Ousman Njie, a boat owner at Tanji.

“We pay tax, still we are not protected by our government. And our income has truly declined.”

About 6 in every 10 Gambians live below a dollar a day, according to the World Bank. For the majority of the poor, fish is their cheapest source of protein. Mamodou Sarr, another artisanal fisherman in Tanji, said the price hikes influenced by scarcity of fish will make fish unaffordable for the majority of Gambians.

A basket of Bonga fish, for example, has increased by over two fold, from D1000 In 2017 to about D2500 in 2023.

In July 2023, the fisheries minister Musa Drammeh, refuted claims that the presence of Senegalese boats in Gambian water is a leading cause of fish scarcity in the country.

He said the agreement has paved the way for both countries to fish in each other’s waters.

“We have only 137 artisanal fishing vessels from Senegal as far as our records are concerned,” said Drammeh.

This story is produced with support from PRJ investigative reporting fellowship, with funding from USG through USAID and implemented by Freedom House. The content of this report does not in any way reflect the views of the US government, USAID or Freedom House. It is the sole responsibility of the author and publisher.