By: Jali Kebba

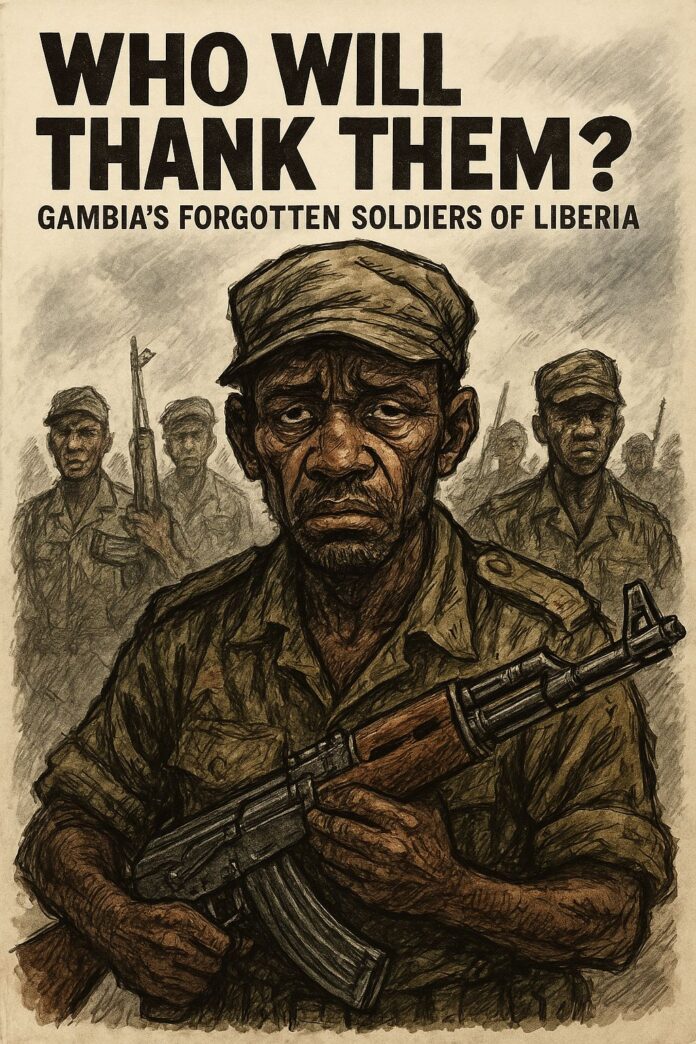

Imagine this. You are in your twenties and part of the Gambia National Army, which is barely 5 years old. You’ve never seen combat. You’ve barely said goodbye to your family. You are given two days of rushed training, handed a rifle, and told that you are going to fight in another country’s civil war.

Then you find yourself standing on a crowded MV Tano cargo ship, surrounded by a coalition of nearly 4,000 soldiers from Nigeria, Ghana, Sierra Leone, and Guinea. Codename: Operation Exodus. It rains almost the entire 30-hour journey. You have no shelter. The food is locked away in the belly of the ship, out of reach. Many of you haven’t eaten. By the time you arrive in Liberia, you are wet, hungry, exhausted—and receiving fire.

And that is just the beginning.

Answering the Call

When the sounds of war and cries of death in Liberia reached an intolerable level, the Heads of State Summit of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), held in Banjul, The Gambia, had no choice but to act. In June 1990, they authorized the creation of an intervention force: the ECOWAS Monitoring Group (ECOMOG). Its mission was clear—stop the factional fighting and create the conditions for a political solution. The Gambia, small as it is, answered the call.

But our soldiers were not prepared for what lay ahead. They were trained neither for counterinsurgency nor guerrilla warfare. They had little to no deployment experience. At a minimum, they should have conducted mission-specific training, weapons qualification, battle drills, communication checks, medical readiness, and logistical preparations—basic steps that provide soldiers the best chance for mission success.

And yet, they went without adequate preparation—representing a nation of barely 1.2 million people at the time, standing among regional giants like Nigeria and Ghana.

The First Losses

The conditions upon arrival were unimaginable. Soldiers are used to tough environments, but this revealed a complete lack of planning. So many critical elements were missing: no toilet facilities, insufficient food and drinking water, and little to no means of communication with higher headquarters back home.

Within two weeks of arriving, two Gambian soldiers were killed in action. Despite the chaos, their comrades honored them the best they could. In the middle of a warzone, they were given a 21-gun salute. At first, they were buried within Freeport in Monrovia, where the contingent was stationed. Years later, the Second Republic arranged for their remains to be repatriated to The Gambia, where they now rest.

Imagine the weight of that moment for their brothers-in-arms—fighting side by side one day, performing burial rites the next, and then returning to the battlefield without pause.

Bravery Amid Hardship

Those who remained never wavered. They fought fire with fire, earning the respect of their fellow West African contingents. They saw things no one should ever have to see—dogs feeding on human remains, children carrying weapons, entire neighborhoods reduced to rubble.

And beyond the battlefield, the hardship was relentless. Gambian soldiers were paid only $3 a day, and for more than 70 days at one point, even that pay never arrived. They survived by trading sardines with Nigerian soldiers for beans and gari. Sometimes, they had nothing at all.

While other nations rotated their troops every 3 to 6 months, the Gambian contingent stayed for nine months straight—nine months of hunger, uncertainty, and fear. Nine months of standing tall while everything around them collapsed.

A Bitter Return Home

Even returning home was not the relief it should have been. There was no welcome. No debrief. No official thanks. Their service was swallowed by silence.

Rumors spread—allegations of looting, whispers of a coup plot. When they protested the non-payment of their allowances, seven were dismissed immediately after receiving payment. Others were told they would never be promoted again if they remained in service.

The Highest Honor

As someone who has been to combat, I can tell this: nothing – no training, no briefing, no speech – truly prepares you for it. The first time rounds crack past you, the world narrows to noise, dust and adrenaline. It is terrifying. It is chaotic. It is exhausting in ways that strip you to your core. And yet, within that crucible of fear and fatigue, survival carries a strange and sobering exhilaration – a bond with your comrades and a clarity about service that few will ever know.

But beneath all that, one enduring truth remains: there is no higher honor than wearing the cloth of your nation in its defense. The military is a profession. And those who do it don’t get paid well. They do it for something bigger than themselves that no one else in the society is willing to do. They have a professional code of ethics and values that is embedded in each individual. And if those get violated, they face discipline and even dismissal.

The Gambian soldiers who went to Liberia may not have received the training, equipment, or preparation they deserved. But they showed courage that demands respect. They stood firm when the odds were against them. They gave pieces of themselves so that The Gambia could stand with its neighbors in a moment of crisis.

It Is Not Too Late

More than three decades have passed, and yet their stories remain largely untold. Many Gambians don’t even know the price that was paid in their name.

But it is not too late.

We can still honor them. We can teach their stories in our schools. We can recognize them publicly on Armed Forces Day. We can build a memorial to those who served—and especially to those who fell.

Because a grateful nation must not forget.

Final Thought

When I imagine those Gambian soldiers on that rain-soaked ship—hungry, cold, uncertain of what awaited them, but still standing—I see the essence of service.

They didn’t get the thanks they deserved. But maybe, just maybe, we can start now.

To every Gambian soldier who has worn the uniform, whether in Liberia or at home. We see you. We honor you. And we thank you.