by Baboucarr Fallaboweh

The sudden cancellation of the Youth League final between Team Rhino and Fortune raised more than a few eyebrows, yet neither the organisers nor the Gambia Football Federation (GFF) offered an explanation.

What began as a single unanswered question soon unravelled into a deeper investigation. The Alkamba Times uncovered a proposed agreement that, while the final remained in limbo, saw Afriksaut secure a fresh three-year partnership with the Gambia Football Academy Association (GFAA).

According to national U17 coach Yaya Manneh, Afriskaut had already reached out to him while he was in Morocco with the youth side. In pursuit of answers, The Alkamba Times contacted the GFF, Afriskaut, the Ministry of Youth and Sports, as well as several stakeholders and agents, to determine whether Afriskaut’s proposals were, in essence, a veiled form of Third-Party Ownership (TPO) – a practice frowned upon by FIFA.

The investigation reveals a striking detail: Afriskaut’s role had evolved from a conventional partnership to a sponsorship arrangement that, according to documents reviewed, included a contentious clause: the company would be entitled to 55% of any future transfer fee for players competing in its sponsored league – a clause that raises serious questions about the balance between grassroots development and commercial control.

Afriskaut positions itself at the crossroads of African football and cutting-edge technology, delivering precise data-driven insights on emerging talents across the continent. By equipping clubs, agents, and scouts with a powerful digital scouting platform, the company aims to transform recruitment decisions- turning raw potential into a recognised opportunity.

Scenario One (Youth League)

Afriskaut entered the Gambian football scene through Ibidapo Olamilekan Quadry of Revolution Sports, who acted as the intermediary between the GFF and Afriskaut. The partnership centred on organising a youth league in the country.

However, Afriskaut representatives made it clear to Quadry that their investment in the competition is hinged on the GFF’s willingness to honour the agreement and work in full collaboration with them.

Afriskaut’s CEO, Naemo, personally wrote to the GFF, prompting follow-up discussions that saw General Secretary Lamin Jassey escalate the matter to the Federation’s Executive Committee. In response, the committee appointed a technical team to engage directly with Afriskaut and explore the proposal in detail.

The GFF’s Youth League operations were staffed by Ebrima Suwareh, Media Communications Officer; Alagie Nyassi, Youth Football Coordinator; Pa Sulay, Competition Director; and Seedy Manneh, Referees Manager – all serving on the Organising Committee alongside Quadry.

Although the GFF’s spokesperson claimed Afriskaut’s dealings were limited to junior staff, those same staff members ultimately report to the Federation’s senior leadership. This raises the question: is the GFF hierarchy using its junior personnel as a buffer to shield senior officers from scrutiny over the Afriskaut affair?

The Federation itself signed a partnership agreement, whose final match has yet to be played yet simultaneously allowed an elite association under its watch to secure a separate sponsorship deal. After all, Yaya Manneh would be unlikely to engage with Afriskaut without the explicit approval of his employers.

Under the agreed plan, the GFF pledged to provide branding and regular updates on its website, while Afriskaut would take full responsibility for streaming, budgeting, and other logistical needs. To this end, Afriskaut transferred $4,000 to Revolution Sports to organise the league and also covered payments to Eye Africa for live streaming services.

Sources allege that Quadry pocketed the $4,000 sent by Afriskaut, acting as though no such funds had ever been received. The only recorded expenses, according to witnesses, were for a single meeting – covering water, biscuits, t-shirts, match balls and banners.

The league’s opening week went ahead without referee payments, while logistical costs were borne by the technical team. Over the weekend, Quadry claimed the money would arrive by Tuesday 21st January, despite already receiving the full $4,000. He is also reported to have stayed at the Football Hotel for a period without settling his bill.

On Tuesday 21st January 2025, Youth Football Coordinator, Alagie Nyassi contacted Quadry, warning that funds used to pre-finance the weekend’s matches needed to be reimbursed or the tournament would grind to a halt the organisers, he stressed, did not want to accrue debts. Shortly thereafter, Quadry left the country and exited the Organising Committee’s Whatsapp group, effectively forcing the suspension of the entire competition.

Ebrima Suwareh, the GFF’s Head of Communication and Afriskaut’s primary contact in The Gambia, informed Naemo of the situation and arranged a conference call with the Organising Committee. During the discussion, Naemo stated that the funds had been transferred on 28 December 2024 and acknowledged he would bear the financial loss. Having already invested in the project, he expressed his desire for the league to proceed despite the setback.

Afriskaut later issued fresh payments to Lamin Kanteh, CEO of EYE AFRICA TV, and a partner in Nigeria the funds — totalling D67, 000 — deposited in four instalments into his GTBank account. The first payment was used to settle outstanding debts, covering costs for the ambulance service, medics, and coordinators.

However, a contentious clause in the Youth League agreement stipulates that Afriskaut holds exclusive rights over the transfer of negotiation of any player who participated in the competition. This has prompted calls from clubs for the clause to be reviewed — and for all agreements to be paused until further scrutiny is applied.

Several clubs voiced concern that the percentage Afriskaut is demanding from future player sales is excessively high. In response, Afriskaut insisted that it would not stage the league final until the clubs signed its contract, arguing that proceeding without such an agreement would amount to operating at a loss.

Below are the few conflicted clauses……

7.2 The Participating Football Club agrees to immediately release and transfer any Selected Player to any other football club nominated by Naemo Sports and the following terms shall be included in the release and transfer document:

7.2.1 The release and transfer of the Selected Player to the football club nominated by Naemo Sports shall be a free transfer.

7.2.2 An obligation to transfer the Selected Player back to the Participating Football Club if Naemo Sports is unable to facilitate an international Player Transfer for the Selected Player at the end of the duration of this Agreement or if the Participating Club is able to independently secure a Transfer with a higher commercial value for the Selected Player subject to clause 7.7

7.2.3 A right to receive 40% of the Transfer Fees and/or 40% of sell-on fees received by the football club nominated by Naemo Sports in respect of the Selected Player from any foreign football club to which the Selected Player is transferred for financial consideration.

7.3 The international Transfer of any Selected Player shall be negotiated and implemented solely by the football club nominated by Naemo Sports.

Evidence suggests that Afriskaut has been operating in The Gambia in the manner consistent of a player agency – a role explicitly outlined in the contract shared with clubs and academies.

An email obtained by The Alkamba Times, allegedly sent by Nnamdi to a Gambian scout, appears to reinforce this impression. In it, he wrote:

“Afriskaut is Africa’s largest football data and scouting platform. We have over 20,000 players across eight countries, working directly with federations and academies. We have exclusive access to unrepresented talent that could perfectly fit your network. We help agents like yourself see top emerging talents and close more deals.”

The language of the correspondence, coupled with the contractual terms, raises further questions about whether Afriskaut’s involvement in Gambian football blurs the line between data-driven scouting and outright player representation — a practice subject to strict regulations under FIFA rules.

GFF Head of Communication, Baboucarr Camara, maintained that the youth tournament was merely a pilot project — and that he was unaware of Afriskaut’s reported demand for a 60% sell-on clause.

“We’ve not signed anything with Afriskaut. This is just a pilot project to see its success before we commit ourselves to a deal,” Camara said. “We instituted what’s called an organising committee of junior staff from the federation, which comprises representatives from the competitions department, communications, technical, and referees’ department.”

According to Camara, the arrangement with Afriskaut’s representative at the time, Mr. Quadry, was clear from the outset: no formal deal would be signed until the program concluded and the technical department had reviewed the competition and issued a recommendation.

“There’s no financial benefit to the GFF. We just gave them approval to go ahead with the competition,” he said. “The contract he wants to sign with us is a partnership agreement that would give him the right to organise this competition for five years and grant them the audio and video rights of the First and Second Divisions.”

Camara added that Afriskaut’s Nnamdi had expressed a desire for the contract to be signed ahead of the final so he could attend the match — a request the GFF resisted. He further stressed that Afriskaut’s attempts to negotiate with clubs for a share of future player sales were private dealings, entirely separate from the Federation.

Concerns Over Contracts

Lamin Kanteh, CEO of Eye Africa TV, said he quickly became wary of Quadry’s role.

“I saw some irregularities and insisted on dealing with Nnamdi Emefo directly,” Kanteh explained. “Before the league started, they shared a contract document that people were not happy to sign, but they continued with the tournament. What they are requesting is too much. How can a club develop a player, and the next minute Afriskaut takes a percentage they didn’t even work for?”

Kanteh noted that even in the GFAA Youth League, some academies — including Menmar — refused to sign, citing concerns over clauses granting Afriskaut exclusivity rights they were uncomfortable with.

“We have come to terms; they lifted some of our concerns and shared a new contract,” he said. “People thought I was complaining unnecessarily, but I wanted academy owners to have their rights protected. Someone subventing your league doesn’t mean they should take full ownership. You cannot develop your player, play five to seven games in a tournament, and then be told the organiser will get a percentage of any sale.”

Kanteh added that while he was accused of causing delays and stirring problems, his aim was to protect the long-term interests of all academies involved.

Media Involvement

Quadry also contacted journalist Ebrima KB Sonko, asking him to recruit four other reporters for coverage, promising each D2,000. Sonko, who attended the workshop and received the payment — which Quadry described as a “gift” — later shared the contract documents and emailed teams, urging them to join the youth tournament.

Sonko says he only met Quadry twice: once at the workshop and once at the youth league’s kick-off.

Fact Check: Senegal vs. Afriskaut’s Claims

In earlier discussions, Afriskaut’s Nnamdi claimed the organisation was already operating in Senegal. However, Senegal has an established and fully functioning national youth league system. In 2025, CasaSports and Wallydan were crowned winners of the cadet tournament.

Senegal’s youth football competitions run year-round, covering U-15, U-17, and U-20 categories for boys and U-15 and U-17 for girls. Matches are structured in league formats and staged across the country’s 14 regions.

National youth leagues were introduced in Senegal in 2020, funded by the FIFA Forward Programme. With the goal of improving the competitiveness of young players and “preparing them for the upcoming 2021 Africa Cup of Nations qualifiers, this year’s competition concluded on the 20th of July with CasaSports winning the trophy.

“This league gives us the visibility we need,” said ASCE forward Mohamadou Lamine Diouf. “We all hope to secure a contract with a big club one day and then be able to help our friends and family. It’s our source of motivation; it’s what pushes us to keep improving.”

El Hadj Wack Diop, Development Manager at the FIFA Regional Office for West and Central Africa, added:

“Young people and girls are often left out. The technical and tactical work is there, and efforts are made by the clubs and academies, but overall they lack competitions. By creating this type of project, we encourage young people from diverse backgrounds to compete against each other. These events reinforce the work already done by the clubs and football academies.”

Afriskaut’s model was initially designed for feeder teams. However, since most Gambian clubs lack such teams, the company shifted its focus to working directly with academies.

Contracts that Youth league clubs refused to sign

(Scenario 2) National Youth U17 league for the academies

“We’ve agreed that Afrisaukt will take 55% and the academies 35% of any future sale they facilitate,” one academy representative explained. “What we didn’t agree to was Afrisaukt telling us which agents we can and cannot work with.

The academies insist on keeping the freedom to speak to agents directly. Under the arrangement, if an academy introduces an agent, the proposal is sent to Afrisaukt, which then has 30 days to find a better offer. If they fail, the academy proceeds with its deal, and Afrisaukt receives no cut.

“We want freedom of talking to agents. We have agreed that whenever we bring an agent. We send the proposal to Afrisaukt who in turn will look for offers better than what is on the table within 30 days. if they fail to do that then the academy will proceed to work with the agent and afrisaukt won’t have any percentage in that deal.”

On April 20, a four-hour meeting was held between stakeholders and GFAA representative Ebrima Touray. According to those present, Afrisaukt’s sponsorship emerged midway through discussions about the commencement of the league, with Yaya Manneh pushing for their proposal as a solution to the lack of funding.

However, some coaches raised concerns, saying Afrisaukt’s rules didn’t align with FIFA regulations.

“Yaya Manneh gave his words regarding the commencement of the league but in between Afrisaukt sponsorship came and he forced people to the Afrisaukt proposals with one factor been lack of sponsorship. Their rules weren’t in accordance with FIFA rules. We agree for one year so that we can review it. Next year they will give all academies some support to prepare for the league,” one coach revealed.

Review of clauses (Review of Adverse Clauses in the GFAA Tripartite Agreement)

1. Unbalanced Transfer Fee Sharing (Clause 7.2 – 7.4)

Issue: Clubs receive only 35% of any transfer or sell-on fee when Naemo Sports is involved, while Naemo gets 55%, and the Tournament Organizer takes 10% if Naemo is excluded.

Impact: This significantly undercuts the academy’s share, despite their primary role in developing the players.

Why it’s bad: Academies invest heavily in player development but receive a minority of the financial rewards.

2. Right of First Refusal (Clause 7.1)

Issue: Naemo Sports has the exclusive right to match any third-party offer for a player.

Impact: This can deter other clubs from making offers and limit the academy’s autonomy in negotiating deals.

Why it’s bad: It restricts the club’s freedom to act in the best interest of their players and could delay or derail opportunities.

3. Exclusive Control of Data and Media (Clauses 4.2, 4.3, 4.4; Intellectual Property Section)

Issue: Naemo holds exclusive rights to data, media, and video content, including player performance analytics.

Impact: Clubs cannot use their own match footage or data for marketing players elsewhere or for internal development purposes without Naemo’s consent.

Why it’s bad: Limits the academy’s ability to promote their players independently or build their scouting reputation.

4. Use of Player Likeness Without Compensation (Intellectual Property Section)

Issue: Players (through the club) must give Naemo a perpetual, royalty-free license to use their likeness and performance for marketing.

Impact: No direct financial or reputational benefit flows back to the players or clubs.

Why it’s bad: Exploitation of players’ image rights without offering them value or protection.

5. No Say in Tournament Scheduling (Clause 2.3)

Issue: The tournament organiser can modify or reschedule matches unilaterally.

Impact: Clubs may face logistical issues or short notice changes without input.

Why it’s bad: Lacks procedural fairness and may burden already resource-limited academies.

6. Undefined Termination Clarity (Clause 11)

Issue: Grounds for termination are broad, but recovery of investment or damages isn’t guaranteed.

Impact: If an academy exits or is removed from the agreement, they may lose all associated rights or benefits with no compensation.

Why it’s bad: Exposes academies to risk with little recourse.

7. Obligatory Data Collection Burden (Clause 6.3.1)

Issue: Clubs must collect and submit extensive data on each player, which could be administratively and financially burdensome.

Impact: Places heavy workload and resource responsibility on smaller academies.

Why it’s bad: Not all academies may have the capacity to comply without additional support.

These clauses, while potentially justifiable from Naemo Sports’ or GFAA’s perspective, heavily favor the tech platform and undermine the long-term sustainability and independence of the academies.

Third-Party Ownership (TPO) — where an outside investor acquires a share of a player’s future transfer value — has been outlawed by FIFA since 2015 to protect player rights and maintain fair competition.

Article 18 of FIFA’s regulations makes it clear: “No club or player shall enter into an agreement with a third party whereby a third party is entitled to participate, either in full or in part, in compensation payable in relation to the future transfer of a player… or is being assigned any rights in relation to a future transfer or transfer compensation.”

Before the ban, TPO deals typically involved investment funds, companies, or individuals providing clubs with cash — often to finance transfers — in exchange for a percentage of a player’s economic rights, effectively turning footballers into shared financial assets.

After reviewing Afrisaukt’s proposed clauses alongside remarks from GFF’s communications head, Baboucarr Camara — a self-described champion of the Youth League — one football stakeholder argued that the federation’s technical department should have thoroughly vetted the deal. “It shouldn’t be left entirely to the clubs to interpret such a contract,” he said. “The GFF is the sole footballing authority, and they failed to protect their members.”

He called for clear national regulations to safeguard young players’ contractual rights in line with FIFA rules, and proposed the creation of a dedicated sports tribunal to handle disputes.

“There must be established regulations in place to protect and guide young players in contractual matters, especially in line with FIFA. Additionally, creating a sports tribunal in the country will help curb the issue.

“The government and FF should support and help fund academies and players in a bid to counsel players and academy owners on their rights, ways of mobilizing resources, and partnerships. It is important for both partners to educate stakeholders vis-à-vis player rights, contracts, and transfer regulations. The FF should monitor every transfer process; this will help in the fair and equal distribution of solidarity fees.”

Yaya Mannehs reactions

Fresh from his team’s 2–1 defeat to Uganda in the FIFA U17 World Cup playoff, Gambia U17 head coach Yahya Manneh delivered a blunt message: without a proper youth league, the country’s football dreams will keep stalling.

“We need a youth league in The Gambia that will keep these players competing regularly,” Manneh stressed. “It will allow us to select players within the correct age brackets and help us build a more competitive team.”

Manneh, who also wears multiple hats as president of KG5 Sports Academy, chairman of the West Coast Academy Association, and president of the Gambia Football Academy Association, has been campaigning for a nationwide youth structure long before taking the U17 job.

“I called for youth league structures because there is no youth league in The Gambia,” he said. “We initiated this in 2022. Back then, I wasn’t even thinking of becoming the U17 head coach. Last year, we played the first edition with the support of the federation and the ministry. We had a proposal from Afrisaukt, and we took it. But in truth, no country can develop without having structured grassroots systems.”

Manneh explained that the first edition began within the Kombos but plans are in motion to expand. “We are in contact with all regional associations,” he said. “We will go to every region to conduct sensitization and help them establish their own youth tournaments. The West Coast has been running its own for the past eight years. We are not going to work with individuals — only with recognised regional associations.”

“The issue of Afrisaukt having 55% of any future player sale is because it was unanimously agreed by the clubs when they sent us the proposals,” a GFAA representative explained. “We called a meeting, laid everything out to the teams, and they agreed to work on it. Our role as an association is simply to facilitate and make sure teams fully understand what the agreement entails.”

According to the GFAA, Afrisaukt’s share reflects its commitment to fully fund the tournament for the next three years, as well as cover the cost of player travel for potential transfers.

“We’re happy that Afrisaukt is not just acting as an agency or scout,” the spokesperson added. “They’re creating a platform for young players to showcase their talents. With enough competitions, these lads can develop into top players.”

The GFAA also revealed plans to expand the youth league nationwide — a move that will require more funding. Under the current arrangement, the association will take 10% of any player sale to finance regional football academy associations. “If we have these funds, every region can run its own tournaments and support its executive committees with basic administrative needs,” the GFAA said.

“The budget for the U17 tournament stands at D700,000, covering administration, referees, match commissioners, awards, equipment, and venue costs. This figure, prepared by the GFAA for Afrisaukt, does not include video production or other technology expenses.”

Lahaiba Kujabie Walks Out Over Afrisaukt Contract

When the fixtures were released and teams knew exactly who they were playing and when, the focus was on football — until, suddenly, a new document arrived from Afrisaukt.

“They wanted us to sign it before we could move forward,” recalled Lahaiba Kujabie. “Everything stopped. We were invited to a signing ceremony, but I walked out. I wasn’t satisfied with the clauses and conditions in that contract. I don’t know Naemo or Afrisaukt, and I’ve never spoken to them. All my dealings, including my registration, were with the GFAA.”

For Kujabie, the timing and scope of the agreement felt completely wrong. “Sponsoring the league is fine,” he said. “But during the league, if they spot a player they want, they can bring a contract for that player. What you can’t do is put the entire 30-man squad in an agreement — for what purpose? To me, it doesn’t make sense. If GFAA wants a deal with Afrisaukt, fine — that’s between them. But we should keep that contract outside the system. I want to deal with a player directly once an offer or proposal comes.”

He believes the process lacked proper scrutiny. “Football managers want to work with standards. We want to give every scout a chance, whether local or international. I don’t think anyone read the document; it was just sent out for academies to sign. If they had read it, they would have said, ‘this isn’t good.’”

The length of the deal was another sticking point. “You always need a legal adviser. We can’t just sign a five-year contract lasting until the end of the European market in 2030 — that’s too much,” Kujabie stressed.

What frustrates him most is the lost potential. “This could have been one of the best leagues for scouting players if it was structured properly so no outsider could come in and fool us. The credibility isn’t there — the contract documents have been changed too many times.”

Still, Kujabie insists his motivation is simple: “For me, it’s about seeing these players go to another level — that’s what matters. But the way this contract is, it’s like we’re handing them over until 2030.”

Youth League Delays, Prize Money Disputes, and Unanswered Questions

What was meant to be a smooth start to the Gambia’s Youth League quickly turned into a drawn-out saga. Originally scheduled to kick off on April 26, the competition didn’t actually begin until May 11 — and it finally wrapped up on July 26.

The qualifiers were staged at the regional level in West Coast, Kanifing Municipality, and Banjul. Each participating academy paid D3,000 to enter the qualifiers and D8,000 for the main competition. The prize promises were ambitious: D100,000 for the champions, D50,000 for second place, and D25,000 for third.

But when the final whistle blew, the promises had evaporated. Excellence Academy were crowned winners of the first edition — yet no cash prizes or awards were handed out, despite the Gambia Football Academy Association (GFAA) confirming it had received D700,000 as part of the partnership package.

In July, months of online debate about the league’s handling spilled into the open. Afrisaukt’s Nnamdi visited The Gambia on the 9th and 10th, hosting a seminar at the Football Hotel in Yundum titled “Unlocking Gambian Talents: Building the Pathway to the Global Stage.” The room was filled with club presidents, academy leaders, and secretaries — especially those eyeing qualifiers for the next edition.

Yet one glaring omission hung over the event: the Youth League final was never discussed. Hopes faded, and with them, the credibility of the competition. Who would hold Nnamdi accountable? And was the GFF quietly positioned to take 20% of any player transfer from the Youth League?

Despite the unresolved final, Afrisaukt pressed ahead, using the GFF’s platform to organize the U17 Youth League and publicly celebrating the trials and achievements of players like Modou Lamin Jammeh of Baliyma FC. Jammeh was among those selected by Afrisaukt — but the full list of chosen players was never shared with The Alkamba Times, despite repeated requests.

Eventually, the names emerged — not through official channels, but via a third-party source.

National U17 Youth Tournament Selections:

- Adama Conteh – LB, Gifts FA

- Modou Lamin Jammeh – MF, Baliyma FC

- Sulayman Kandeh – CF, Excellence Academy

- Sellou Jeng – RW, KG5 Sports Academy

- Hamidou Faye – CF, KG5 Sports Academy

- Muhammed Danso – LB/CB, KG5 Sports Academy

Youth League Selections:

- Buba Baldeh – CB, Brikama United

- Abdoulie Njie – CF, Greater Tomorrow

- Abdou Wadou Sarr – CB, KG5 Sports Academy

- Yankuba Touray – CB, TMT FC

- Baboucarr Manneh CF LW RW Samger FC

- Kawsu Singhateh ACM Fortune Fc

The list is now public. But the bigger questions — about transparency, governance, and who truly benefits from this youth football showcase — remain unanswered.

Voices Of The Academies

Youth football is the foundation of the game — get it wrong, and the cracks will run all the way to the top. In the Gambia, that foundation is shaky. Decisions made today, coaches and administrators warn, could shape not just careers, but the future of the sport in the country.

“We have very good players,” one veteran coach told The Alkamba Times. “Everyone knows the Gambia produces talent, and that’s why everyone is rushing here. But without structure, we’ll lose many of them.”

The recent Afrisaukt youth tournament — meant to be a showcase for grassroots talent — has instead left a trail of frustration and mistrust. What should have been an opportunity to elevate young players has been clouded by disputes over contracts, revenue shares, and selection processes.

Contracts and Controversy

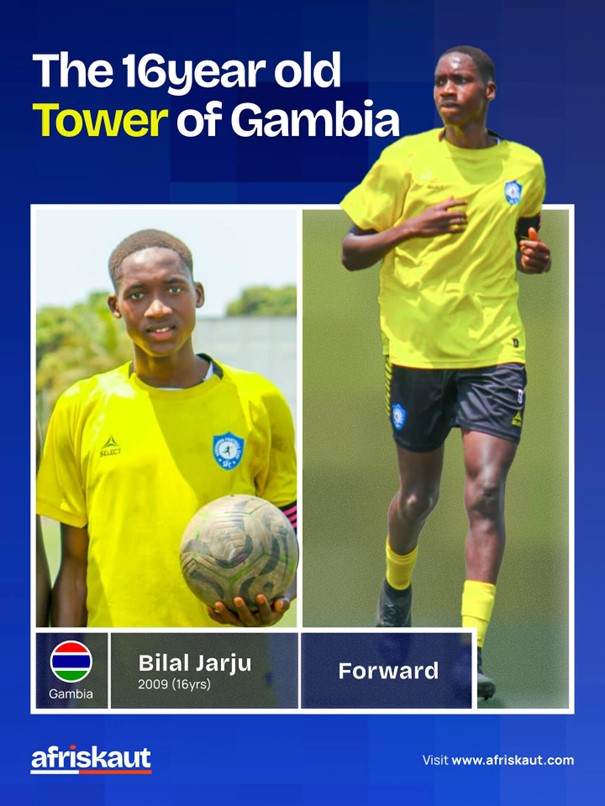

One of the league’s standout players, Serekunda FC’s Bilal Jarju, scored nine goals in six matches and has already attracted interest from German side Bayer Leverkusen. But his club is pushing back against Afrisaukt’s terms, which would give the organizers 60% of any deal.

“That’s impossible,” said the club’s technical director. “We spend D600,000 on training. We’re suggesting an 80-20 split instead. We don’t want to tie Bilal to one agent or offer.”

Afrisaukt’s CEO is reportedly negotiating with wealthier clubs while holding firm on tougher terms for smaller, less resourced academies. Some see this as the heart of the problem: a lack of fairness and transparency in a system already stretched thin.

The future is bright, and it’s wearing Gambian colours. 🇬🇲

Selected from the Afriskaut Gambia Youth league Cup Competition, these two young talents are set to ignite the Gambia U-17 squad with raw skill, passion, and untapped potential! ⚽️ pic.twitter.com/sjJKBxQAvt

— Afriskaut (@afriskaut) March 10, 2025

The Missing Grassroots Framework

For Nenet, a technical member at Daranka Future Academy, the deeper issue is the complete absence of a dedicated grassroots football department in the Gambia.

“My academy has existed since 2014, but I’ve never seen an official grassroots setup,” he said. “We’re the foundations, yet we’re neglected. Without proper early development, players struggle later, no matter how talented.”

He points to players like Nicholas Jackson — gifted, but criticized for lacking certain technical basics. “Our players jump from nawettan to divisional football, where results are everything. There’s no time to nurture them.”

Nenet argues for year-round league formats instead of occasional knockout tournaments, with structured training to build fundamentals. “Grassroots football needs to be watered and taken care of. We should have coaches teaching how to move with or without the ball, how to control, pass, and think the game.”

The Cost of Playing the Game

For some academy managers, the struggle is financial. A Banjul-based coach, speaking on condition of anonymity, described the costs of competing: “We play all our games away. Transportation is D2,000 per match, breakfast another D1,000, water D600, laundry costs on top. Our budget is at least D4,000 per game. Multiply that by 11 matches — it’s draining.”

Even worse, some say they are being excluded entirely. A West Coast club official claims his academy hasn’t been invited to regional tournaments or U17 screenings. “Half the U17 squad came from one person’s academy,” he said. “You can’t be the player and the referee at the same time.”

Power and Politics in the Academy System

Several academy owners accuse top football administrators of serving their own interests. One coach, who regrets opening his academy, blames the lack of respect from leadership. “When we say grassroots, we mean academies — but here, people bypass us. The GFF should organise U17 tournaments, not leave it to private deals.”

Others highlight the conflict of interest in leadership. “The chairman of the Academy Association is also the U17 coach and runs his own academy,” another coach noted. “Before signing with Afrisaukt, he should have consulted us. Instead, the league was delayed, and the deal doesn’t benefit us.”

The School vs. Academy Debate

Baboucarr Mbye, youth coordinator at Kunkujang FC, says the Federation is undermining academies by crediting school teams with developing players. “It’s a system failure,” he said. “Other countries take academy kids directly. Here, a player trains with an academy for years, but when he makes the national team, his name appears under a school.”

For Mbye, this is about more than recognition — it’s about player development. “Schools don’t have year-round football programmess. Some don’t even have jerseys. PE teachers borrow equipment just to play knockout tournaments. That’s not how you build a footballer.”

A Call for Standards

From Bilal Jarju’s contract dispute to the lack of grassroots investment, the message from coaches and academy owners is the same: without a structured, fair, and transparent system, Gambian football will keep wasting talent.

“We train these kids from eight to seventeen,” one academy manager said. “We do it with passion, with no guarantees. All we want is a system that respects the work we put in and gives every player a fair chance.”

Until that happens, the country’s most promising players may keep slipping away — not because they weren’t good enough, but because the system wasn’t.”

Voices of the agents

As the Afrisaukt National Youth League plays on, the noise outside the pitch is growing louder than the cheers in the stands. Questions of legality, ethics, and conflicts of interest now dominate the conversation — and some insiders say the stakes could be nothing less than the future of Gambian youth football.

Agents Sound the Alarm

Speaking to The Alkamba Times on condition of anonymity, one Gambian football agent said the current arrangement between Afrisaukt, the Gambia Football Academy Association (GFAA), and local academies violates FIFA’s own rules.

“As an agent, it’s illegal for any representative to take more than 10% commission,” the agent explained, citing the new FIFA Football Agent Regulation (FFAR). “Any unlicensed person or company offering football agency work and charging for it is doing something illegal. Afrisaukt claims to be a scouting or data company, but what they’re doing is unlicensed agent work.”

TPO “A financial interest in the future transfer of a player’s registration.”

Under FIFA standards, he added, Afrisaukt should receive no more than 5–10% from any deal, with the majority of revenue going to the academies who develop and train the players.

“These academies spend years — and huge amounts of money — building these players,” he said. “For Afrisaukt to demand more than the academies themselves doesn’t make sense. It’s like third-party ownership, which FIFA has banned. Agreeing to this could risk academies being sanctioned or banned.”

The agent also accused U17 national coach Yaya Manneh of a clear conflict of interest. “How can the national team coach run an academy association and partner with Afrisaukt, then claim to be neutral in player selection? Of course he’ll give preference to players from this tournament.”

Beyond selection bias, the agent questioned whether parental consent had been obtained for the use of players’ image rights — rights which, he warned, could be commercially exploited without the players’ or parents’ knowledge.

“It’s Illegal” — A Second Agent Weighs In

A second agent, also requesting anonymity, echoed the concerns. “What Afrisaukt is doing is illegal. You cannot claim economic rights over a player who doesn’t play for your team,” he said.

He pointed to Eyeball, a separate platform offering similar scouting exposure without charging Gambian teams. “All you need is to send your video links and match sheets — no financial strings attached,” he said, urging the government to decentralise support for grassroots football.

In his view, Ballers for Life (B4L) — a rival youth competition — is “bigger, better organised, and more competitive” than Afrisaukt, with fewer conflicts of interest.

B4L’s Different Approach

B4L co-founder Badara Sowe says his tournament is built on structure and player welfare. “When we came in, we found structural issues and capacity gaps. Some academies weren’t even registered or affiliated with authorities. We help with that, ensure parental consent, and provide contracts for players,” she said.

For Sowe, the priority is providing a safe and productive platform for youth players. “Our interest is the footballers first, then everyone else. We want a national youth and school league that develops ready-made talent for the national teams. The idea is to give kids the basics, a platform to showcase their skills, and a path to professional opportunities.”

By 2029, a total of 12,807 players are expected to be exported from Africa will cost just about 15,000 Dollars but Africa with Afriskaut 8,595 players to be sold at minimum 100,000 Dollars Africa will make 860 Million Dollars for the continent, and Gambia with Afriskaut the Academies and Clubs will make between 15 to 22 Million Dollars for the transfer of 197 to 288 players.Nnamdi CEO OF Afrisaukt

Calls for Collaboration

A journalist who covers both U17 leagues says the rivalry is counterproductive. “It’s two people doing the same thing separately. If they collaborated, it would be more powerful and organized. There are B4L players who could walk straight into the junior national team,” she said.

She noted that Afrisaukt’s league is largely urban-based, while B4L is decentralised and includes provincial teams — a crucial factor, he argued, for discovering hidden talent. “Look at Mahmud Bajo — from the provinces. Without access, you’d never see that talent.”

Money and Motives

The two tournaments differ in scale and cost. Afrisaukt reportedly spends D700,000 (excluding video coverage), with a D8,000 academy registration fee. B4L runs on about D400, 000, charges D10,000 per team, and uses a single venue, Brikama Box Bar Mini Stadium.

Some clubs say they were blindsided by Afrisaukt’s approach. “I received their email, but told my secretary not to respond,” one academy owner said. “I don’t like the corruption in football. We played up to the semifinals, but we haven’t signed anything with them.”

A Game off the Pitch

Between accusations of illegal contracts, conflict of interest, and questions over player rights, the Afrisaukt National Youth League has become a flashpoint for a larger debate about who controls Gambian grassroots football — and whose interests truly come first.

As one agent put it bluntly: “I can’t be the player, the coach, and the referee. In this case, that’s exactly what’s happening. And in football, that never ends well.”

Videos Being Sold To Poor Academies Kids

Afrisaukt has begun selling match clips from the National Youth League for D1, 500 each. International clients subscribing to the Afrisaukt platform are reportedly paying significant sums for access to player statistics, match footage, and updates on player availability.

U17 national coach Yaya Manneh maintains that all participating academies consented to purchasing videos of their matches, while Afrisaukt retains exclusive rights to the footage.

However, not all academy heads are convinced. Lamin Kanteh, president of Menmar, defends Afrisaukt’s right to recoup production costs, saying, “Afrisaukt spends money to produce these videos. At the end of the day, giving them away for free would not be cost-effective. On a personal level, I fought against this.”

But Kanteh also acknowledges that this was not the initial understanding. “What was said earlier is that they would provide the videos to any team that was interested. The idea of selling them is a recent development,” he explains.

Menmar has long insisted on keeping its own footage. “I made it clear to Afrisaukt that we could not join this competition without having our videos. I am not developing these players solely for Afrisaukt’s scouts. My project must continue with or without them. I can’t be competing in a league, spending money, and still not have my own archive to review my players’ performances.”

One academy is already scrambling to raise D11, 500 to purchase its season footage. “Initially, they told us we would have access to our videos, but now it’s D1, 500 per game. If we had known earlier, we could have prepared. Paying for 11 matches is a heavy expense,” said one coach.

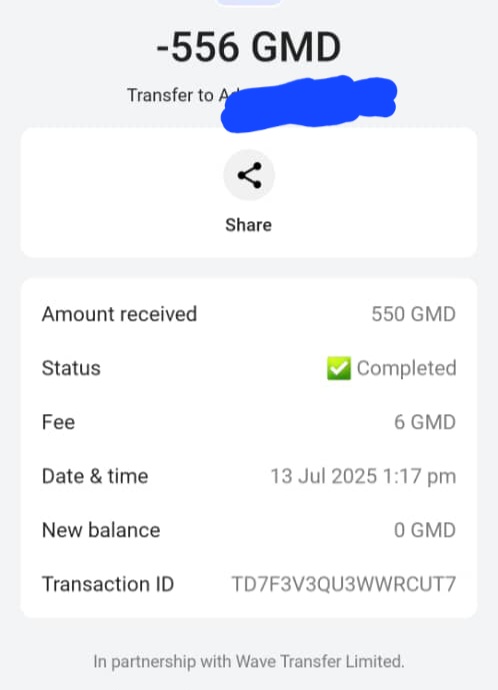

To meet the cost, the academy decided that each player would contribute D550, while the remaining D1, 000 per match would come from the coach’s own pocket. “We are paying so the players can create highlight reels for themselves,” the coach added.

The financial strain is also limiting opportunities for players like Modou Lamin Sarr. “He needs a video, but I don’t even have the money. If I did, I’d pay for it myself,” the coach admitted.

He also expressed frustration over officiating standards. “Some referees are unqualified and make poor decisions. They awarded a penalty against us that I believe was wrong. If I had been filming that game myself, I would have posted the footage on social media without hesitation.”

Kids had to wait between 2 and 6 hours on average before playing

The proposed venues for this year’s Youth League included Kabakel, Basori, Bakau Mini Stadium, Goal Project, and Brikama, with a home-and-away format. However, several teams complained about the lack of logistics to travel between venues. Naemo, representing Afrisaukt, reportedly promised to refund transport costs — a promise that was never fulfilled.

Eventually, the Gambia Football Federation (GFF) stepped in, offering the NTCC field free of charge to host matches.

For the National U17 Youth Tournament, the official venue list featured Serekunda East Mini Stadium, Banjul’s KG5 Mini Stadium, Gambinos Mini Stadium, Brikama Box Bar Mini Stadium, and the Goal Project. In practice, only Bakau hosted a single weekend of matches. The rest of the fixtures were confined to the Goal Project and Brikama Box Bar Mini Stadium, while KG5 Sporting Academy alone had access to the Gambinos facility.

Parents have voiced concerns over match scheduling under extreme heat.

The shortage of playable pitches has disrupted the flow of games, causing repeated delays. Kick-offs were set for as early as 7:00am and 9:00am, but in reality, games often started hours later. Despite receiving FIFA Forward funds, The Gambia still lacks any government- or GFF-owned mini stadium. Most facilities are privately owned by clubs. The GFF claims to have supported the renovation of 14 mini stadiums, but many artificial turfs, lighting systems, and perimeter fences remain in poor condition.

One parent, aged 45, recounted two incidents that left him frustrated and concerned for player welfare. “This U17 tournament is for kids — they’re still vulnerable and not physically strong enough to cope with such conditions. I used to work night shifts and finish at 8:00am. One time in Brikama, my son told me his match was scheduled for 7:30am. They ended up playing at noon under the burning sun.

“Another time, they were told kick-off was 7:00am. I arrived at the Goal Project to find the game hadn’t even started. Instead, there was a test match between SEBEC — with no referee — delaying the entire tournament. That U17 game eventually kicked off at midday. I couldn’t even sit in the heat myself; I had to move to the shade. It broke my heart to see kids running in such humid conditions.”

Parents and coaches say the repeated delays are unacceptable. “Whenever they’re told 7:00am kick-off, they always start at 12. It’s inconsiderate. If these players are meant to represent the national team in future, they should be treated far better,” the parent said. “The organisers have a lot to fix going forward — especially logistics. I am not happy with a game scheduled for 7:00am but played at midday.”

The GFF failed a grassroot football scheme

The Alkamba Times has found that the GFF have failed to effectively implement and sustain its grassroots and talent development programmes — despite millions in available funding and clear objectives laid out in its National Football Development Plan.

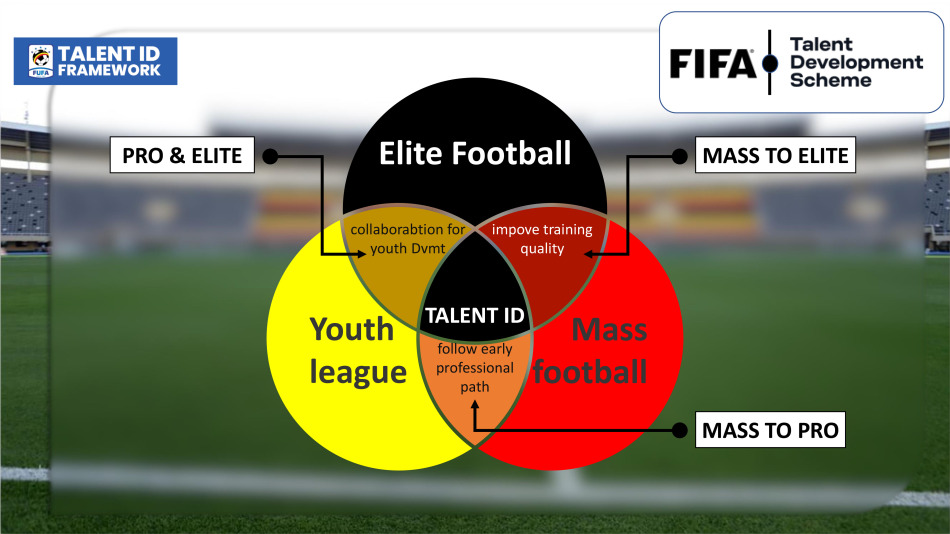

A member of the GFF’s own technical team told The Alkamba Times that the Federation have all but abandoned its FIFA-backed Talent Development Scheme. Launched on 4 March 2022 with the motto “Bridging the Gap”, the initiative was meant to give every promising player a fair chance, identifying and nurturing talent for future U-15, U-17, and U-20 national teams.

It has now been three years, six months, and 27 days since that launch — and no visible progress has been made. The GFF received USD $200,000 for the project, but according to sources, a large portion was allegedly redirected to the senior national team instead of youth development.

“If the talent development scheme had worked as it should, we wouldn’t need Afrisaukt today,” the technical official said. “The project had stages — you do the work, you report it, FIFA releases the next payment. We stopped after the second instalment. From January to March 2025, there was a window to apply for further funding, but we couldn’t, because we had no evidence the programme had been implemented.”

The FIFA scheme was designed with a bottom-up approach: U-13 players feeding into U-15s, and U-15s into U-17s. Trials were conducted across all seven regions, with the best players gathered into regional training centres. These centres were meant to meet every two or three months for follow-up training, eventually filtering the most talented boys and girls into national youth squads.

The plan also called for annual summer championships, where all centres would send their best players to the Goal Project for final selection. But without consistent funding, the programme stalled — and has not resumed.

Meanwhile, countries like Uganda have successfully maintained their talent development projects, producing squads that have beaten The Gambia at U-15 level and even in a FIFA U-17 World Cup playoff.

“Development can’t stop and start — you lose ground,” the technical team member stressed. “Senegal has dozens of pitches; we struggle to find fields even for the national league. Where is the space for a youth league?”

Despite this, President Lamin Kaba Bajo has repeatedly claimed grassroots football is a top priority. The Alkamba Times was unable to find the current National Football Development Plan for 2022–2026.

In February this year, Kaba was among more than 30 African FA presidents in Mauritania for the opening of a FIFA Talent Academy — part of FIFA’s aim to have 75 such elite academies worldwide by 2027.

Under his 2022 objectives, Kaba pledged to improve football infrastructure nationwide through the rehabilitation of existing grounds and the construction of new ones. Yet progress has been patchy. The artificial turf at Banjul’s KG5 Mini Stadium — renovated at a cost of D6 million — was in poor condition after just one year.

Bakary K. Jammeh, who oversaw the project, admitted it was “a good lesson for the future.” Ultimately, it took presidential intervention and a further D30 million of state funds to properly refurbish the stadium.

FIFA’s own Forward Report (2016–2022), published in December 2023, states that USD $2.8 billion was made available to 211 member associations during that period, funding over 1,600 long-term development projects. The GFF has clearly benefited from this scheme — but on-the-ground delivery remains questionable.

One of Kaba’s core NFDP objectives is Grassroots and Youth Football Development. Yet with failing pitches, an abandoned talent programme, and a youth league hampered by poor logistics, the gap between ambition and reality appears to be widening.

FIFA President

We launched [the FIFA Talent Development Scheme] three years ago with a very simple objective: to give every talented player the chance to maximise their potential, regardless of their origin and situation.”

Gordon Derrick Former Caribbean Football Union president

“These projects, when they are executed properly, are of critical importance to the development of the sport in our region,” “They have not always been executed properly, but those that have been working exceptionally well.”

Root causes of the Youth Football development challenges in recent times

A football analyst and co-founder of Jolof Bantaba, Abdoulie Cham, has examined what he believes to be the root causes of the decline in youth football. His assessment follows the failure of the U20, senior national team, and U17 squads to qualify for any major tournament — with the latter only earning a place in the U17 Africa Cup of Nations after finishing third in the WAFU A qualifiers.

Inappropriate Football System & Strategy

The country is fortunate with kids (especially boys) who are passionate and often engage in unorganized/ semi-organized football in the Gambia. Hence, periodically we’ll have strong youth teams competing and qualifying for major youth tournaments. However, the sustainability of producing good teams in this manner is very unlikely. To consistently produce good teams at youth levels, we need a structured system to nurture players.

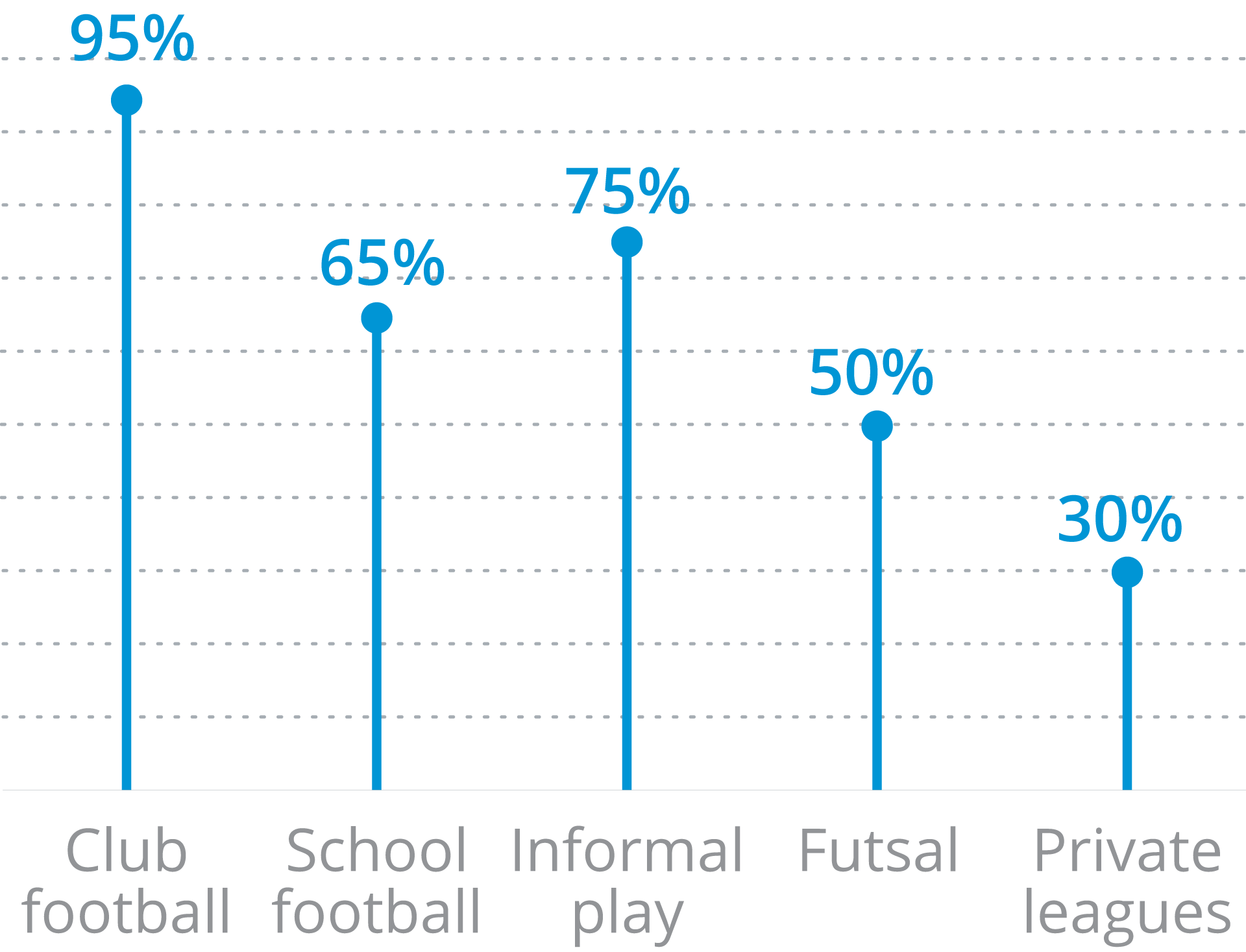

Football development is three stages: grassroots football, youth football, and elite football. Grassroots football is almost neglected in the Gambia, and shades of missing grassroots development can be seen even at our senior national team. We tend to associate youth football with grassroots football, which is totally different and has different development schemes.

of the top MAs incorporate grassroots football in the overall strategy for player development

At the national level, the federation should look to develop a National Talent Center. This center will complement the efforts of the academies and clubs in the country and set the blueprint for development at various levels of grassroots and youth football.

This will require coordination between the ministry of youths and sports, federation, clubs, schools, and private sector. The goal should be to create a sustainable system that will nurture talents from grassroots to elite.

Lack of Football DNA (Credit: Sainey Kanyi)

Every national team in the Gambia operates independent of the other, and there lacks a proper pathway and transition among levels. By having an idea of how we want to play, we can channel our development plans accordingly.

With a Talent Center that houses various categories in all stages of football development, the federation can develop a football DNA on a small scale that can be expanded nationwide through the RFAs.

Coaching Education

The coaching education system should be reviewed as it tends to neglect the grassroots level of development.

Expand our Coaching License Pathway with support from CAF, FIFA, and other National Federation. Our focus should be on grassroots-specific & youth-specific training (grassroots, CAF C, and B licenses).

Other areas that need to be strengthened or introduced are National Youth Leagues, Clubs & Academy Accreditation System, Infrastructure (of course), and School-Football Links.

Uganda’s journey and roadmap

The Federation of Uganda Football Associations (FUFA) has unveiled a strategic plan to become Africa’s leading football nation both on and off the pitch. Central to this vision is a structured grassroots-to-elite development pathway, anchored by a mandatory player development curriculum for all academies.

FUFA will license academies in classes A to D, valid for two years, based on infrastructure, governance, personnel, sporting standards, and finance. Licensed academies must share player data with FUFA’s master database, with each player receiving a unique identification number.

Does the Government Provide Enough Support Through MOYS?

The Gambia Football Federation (GFF) have repeatedly claimed that insufficient government support forces them to shoulder heavy financial burdens, diverting funds intended for development projects into covering national team expenses.

However, Ministry of Youth and Sports (MOYS) Communication Officer Lamarana S Jallow disputes the notion of strained relations, suggesting that media reports have fuelled unnecessary drama. She insists the ministry and the GFF maintain a cordial working relationship.

Speaking to The Alkamba Times on 6th May, Youth and Sports Minister Bakary Badjie referred queries to Jallow, who explained that while government assistance is substantial, it is not limitless.

“Government does not cater for everything,” she said. “When the GFF presented a budget of D15 million, we provided D12 million, covering most essentials such as flight tickets, match bonuses, and allowances. Beyond that, they have special delegations they bring along, and we cannot meet every request—especially when some fall outside our budget lines.”

She noted that the Sports Levy account, a key funding source, is not always flush with cash. Requests are vetted by a committee that includes auditors, accountants, and procurement officers to assess both the legitimacy of the request and the availability of funds.

“The government cannot give money that isn’t there,” Jallow stressed. “We support as much as possible within our means. National teams are the government’s responsibility, but resources have limits.”

Janjanbureh NAM Omar Jammeh

“Looking at the gap in our football sector, we think there is a need to engage GFF to be chipping in and complementing government efforts in football development. If the Senegalese Football Federation is doing it, why not the GFF. Because what we are seeing is that they are sabotaging the government and your ministry”

The ministry, which oversees all sporting activities under the National Sports Council (NSC), explained that funding requests from associations follow a set process: associations write to the NSC, which forwards the request to MOYS. Support is granted based on available funds, but if resources are scarce, the ministry notifies the association or asks them to pre-finance activities with a promise of reimbursement.

“We have different budget items, and urgency plays a role,” the official said. “If something is crucial for the country, we look within the ministry to source the funds—even borrowing from other departments like NEDI if necessary.”

The Ministry’s Contribution Towards Football In The Last Five Years

While acknowledging that both the GFF and government contribute to the national team, the ministry says transparency remains a sticking point. “The federation does not appreciate us publishing how much we give them—they don’t want that transparency. I’ve often been confronted about this, but my duty is to serve both them and the government.”

Minister of Youths and Sports Bakary Badjie

“It is true that we fund the senior national team, and occasionally we support the U17 and U20 teams. Recently, we also provided funding for the women’s team for the first time. When the Football Federation requests a budget of D15 million, we provide D12 million; this is standard practice.

“There are, however, issues around some requests that we do not always agree to or authorise. Occasionally, the Federation reaches agreements with players and informs us afterwards. On one occasion, the budget was D10 million, which we approved, but it subsequently increased to D15 million and later to D20 million.”

MOYS has called on the public, private sector, and philanthropists to support national teams, stressing that football is not solely the government’s responsibility.

“Our budget is the lowest among all ministries,” the official noted. “We’ve always supported sporting disciplines, but now we publish our contributions for accountability and transparency. People need to know what we are doing and what we are contributing.”

GFF Finance: Youth and Grassroots Programmes

An extract from the 2023 Gambia Football Federation (GFF) budget highlights allocations for grassroots and youth football. The Alkamba Times has attached both the 2023 and 2025 GFF budgets, alongside the Ministry of Youth and Sports’ (MOYS) contributions over the past five years (File No. MT19/02 PART 16 [LSJ]), detailing support to various national teams.

The 2024 GFF budget was D122.395 million, while the 2025 allocation to MOYS stands at D155.26 million.

Salaries and Programmes (2023)

- Technical staff (youth coaches, regional coaches, etc.): D150,000 monthly, totalling D1,800,000

- Quarterly Evaluation Meetings—Regional Coaches: March D20,000; July D20,000; September D20,000; December D25,000; total D85,000

- National U15 Youth League (Jan–Jul): D700,000

- Talent Development Scheme Project (Jan–Jun): D300,000 per month, total D1,800,000

Total expenditure on youth and grassroots: D15,825,000

Other contributions:

- FIFA School Football Support Programme (USD 50,000): D3,000,000

- FIFA Funds: D96,000,000

- Football events & competitions—Quarterly Evaluation Meetings: D300,000 (June)

- Support to school football association: D1,562,500 (Jan & Jul), total D3,125,000

- Regional Football Association (RFA) support: D875,000 (Jan & Jul), total D1,750,000

Total figures spent on youth and grassroots:

- 2024: D1,675,000

- 2025: D3,840,000

Promotion of youth and grassroots football:

- 2024: D17,050,000

- 2025: D13,650,000

GFF Senior Finance Manager, Ismaila Njie, explained:

“As far as the youth programme is concerned, the yearly support provided to regional associations should be used for youth programme activities and our youth department initiatives. Regional associations are expected to deliver activities on grassroots and academy development, which constitute a core stream of our operations.

“The technical department sometimes submits proposals to FIFA to run youth activities, such as the Talent Development Scheme and School Football programme, which may attract USD 50,000–100,000 for youth development.

“However, challenges arise when funds intended for youth football are redirected to cover national team activities. GFF is not responsible for the national team’s budget, but shortfalls from government support often necessitate using youth development funds to meet immediate national team needs.

“With FIFA Forward 3.0, there are 11 criteria supported by a financial programme exceeding USD 100,000. Failure to meet these criteria results in six-monthly deductions of USD 50,000. FIFA provides USD 1,250,000 yearly for operational costs. The Gambia also received USD 200,000 as solidarity support for the nine national teams, equivalent to D14 million—enough for only one national team.

“Our national team budget has grown from D22 million to D28 million. While FIFA allocations assume government support for the national team, limitations often force GFF to use development funds to ensure national teams can compete.

“The GFF operates between three stakeholders: the government, primary stakeholders, and the public. While the public expects competitive national teams, stakeholders demand development, and the government seeks results that can yield political goodwill. The major constraint is finance.

“For youth and grassroots football, we maintain a mainstream programme via elite associations, such as the School Football Association and Academy Association. These associations represent GFF in the regions, but full financial support is not possible. It is the responsibility of the regions to submit proposals and raise supplementary funds for grassroots initiatives.”

The Alkamba Times discovered that the outcomes and impact of grassroots youth football do not align with the funds disbursed by FIFA and CAF. Resources that have already been provided should have been utilised effectively to maximise the impact of the CAF development programmes. With the new CAF Impact Programme incoming, questions arise as to why platforms such as Afrisaukt are being accepted.

GFF budget 2023 and 2025 draft

This practice of reallocating funds is common among football federations and governments across the continent.

In Uganda, former international player Dennis Obua fought to retain the chairmanship of the Uganda Football Federation (FUFA) amid allegations of misappropriation of FIFA funds intended for the Youth Development Programme. Obua admitted that most of the grant was spent on the Uganda Cranes’ international travel, as the government does not fund football in the country.

Similarly, a minibus purchased for federation use cost USD 13,140, while a van cost USD 6,286—figures said to have been grossly inflated.

In Kenya, FIFA ordered an audit of the Youth Development Fund in September 2000. The USD 250,000 grant, initiated in May 1999, saw USD 82,000 of transactions unsupported by documentary evidence. Rather than restricting the fund to its intended purpose, USD 40,000 ended up in the federation’s main account without authorisation. FIFA withheld further funding temporarily but resumed after KFF officials justified their request during the World Under-20 Cup in Buenos Aires, deducting the USD 82,000 that could not be accounted for.

CAF Impact Programme

Launched on 26 April 2025, the CAF Impact Programme is a strategic initiative designed to improve transparency and accountability in the use of funds provided to member associations for African football development.

The programme aims to empower member associations, foster the growth of youth competitions, and address Africa’s unique challenges and opportunities. CAF member associations will receive up to USD 1.6 million over four years—a 60% increase from the previous cycle—to support:

- Women’s football;

- Football development and youth competitions;

- School football programmes;

- Operational costs;

- Training, particularly for coaches and referees.

In addition, USD 500,000 in performance-based incentives will be available over four years for each member association.

CAF General Secretary Véron Mosengo-Omba emphasised: “CAF and its President are ensuring that every dollar invested is used to develop African football, with a special focus on women’s football and youth development.”

Grassroots Football in the Upper River Region (URR)

Talent Identification

All motivated and talented male and female footballers should have the opportunity to be scouted, identified, and developed, irrespective of their location, age, or socio-economic background. Every talent deserves a chance

Grassroots football should be accessible and inclusive. However, in the URR, the regional association is largely inactive and poorly organised. Although regional coaches exist, they rarely conduct grassroots or academy-level activities, and school football is largely dormant. Engagement occurs mainly around school tournaments or talent identification screenings, often limited to a few selected clubs or academies over one or two days.

Despite this, there has been a positive development with the rise of academies across the region, even in remote villages. Regional coaches must take an active role to ensure continuous grassroots competitions, enabling young players to gain selection opportunities for U17 and U20 teams.

A notable example is Ismaila Sonko from Basse, who was selected for the U17 team after participating in his school’s tournament in Soma. Numerous other talented players, however, miss similar opportunities due to the lack of structured programmes. Competitions should be year-round, with one tournament following another, providing consistent engagement from school to academy levels.

Recently, a regional academy association was formed, offering a clear direction and structure. Tournaments for academies are now being organised, with increasing participation and commitment. Over time, these initiatives could feed directly into U17 selections, allowing scouts to identify talent from across the region rather than solely the Greater Banjul area.

Star Football Academy: A Case Study

Inspired by local children playing barefoot on dusty fields, Alasan Sarr and Ebrima Jammeh established Star Football Academy in 2018 in the North Bank Region. Starting with only a handful of players on a borrowed family compound, the academy integrated academic education, character development, and health education into its training programme and partnered with local schools.

By the 2021–2022 season, the academy’s U17 team finished as runners-up in the Essau Junior Tournament, while the U15 team won both the league title and knockout trophy in the Mbollet Ba Football Competition, demonstrating the potential impact of structured grassroots programmes when implemented effectively.

In 2023 and 2024, the academy’s U15 team finished as runners-up in the NBRFA Youth Cup, a prestigious tournament showcasing the region’s top youth teams. Additionally, during the 2023–2024 season, the women’s team secured the runners-up position in the North Bank Third Division competition. These accomplishments earned the academy recognition from the North Bank Football Association (NBRFA).

Beyond competition, the academy has successfully reintegrated individuals into the school environment and is committed to providing financial support for their essential needs. The academy also runs outreach programmes, offering free weekend training sessions to underprivileged children. Annual football festivals are organised, bringing together youth teams across the region to promote unity and sportsmanship.

Challenges Facing Football Academies

Football academies in the North Bank Region face several significant challenges that hinder both their development and the growth of young talent. A primary concern is the lack of adequate infrastructure. Financial constraints further exacerbate the situation, as most academies rely heavily on donations, making it difficult to sustain operations or invest in player development.

There is also a notable shortage of qualified coaches and technical staff, which affects the quality of training offered. Many academies struggle with poor administrative structures and lack long-term strategic planning. Additionally, limited support from government agencies and national sports authorities, coupled with scarce opportunities for international exposure, restricts young players’ advancement. Collectively, these challenges limit the potential of football academies in The Gambia.

Recommendations for Improvement

The NBRFA should increase investment in coach education by offering regular training programmes and certification courses in partnership with CAF and FIFA. Improving the quality of coaching within academies is critical, and young coaches should receive structured and professional training from an early stage. Currently, regular coach training has been largely ineffective; for example, over the past eight years, D license coaching courses have only been conducted twice, highlighting a substantial gap.

Furthermore, the NBRFA should ensure that academies operate within established guidelines to maintain consistency in training methods, uphold ethical standards, and facilitate talent progression. Investment in infrastructure, including the development and renovation of training facilities, pitches, and mini stadiums, is essential for enhancing training quality and safeguarding young athletes.

The coaching education system requires review, particularly at the grassroots level. Expanding the Coaching License Pathway with support from CAF, FIFA, and other national federations is vital. Emphasis should be placed on grassroots-specific and youth-specific training, including CAF C and B licenses. Other areas for improvement include the establishment of National Youth Leagues, the implementation of a Clubs and Academy Accreditation System, infrastructure development, and stronger school–football links.

Best Practices and Case Study

Serekunda East Sports Development Organisation stands as a leading example of excellence in organisation, development, and process management. According to the head of the academy, Ebou Lolly, their focus is on providing structured football training and competition. While more than 20 academies operate in the area, many lack proper organisational structures and are not fully equipped to meet basic standards.

Academies such as LK Sports and Gambinos have a clear understanding of their needs and meet the correct criteria. The technical department of the organisation involves the entire committee, headed by the second and third vice presidents.

The tournaments organised by the academy are non-profit. Participating academies receive two footballs and a certificate, while the winning team is awarded D2,000 and four footballs. Additional equipment, such as cones and markers, is also provided to ensure proper training and competition standards.

Access to football

Offering continued chances to play, train and fall in love with the game at every stage is crucial to the growth and development of football.

One of the major challenges faced by academies is the lack of structured organisation. Many academies operate without a technical team, often leaving a single individual to manage all aspects of training and administration. Age cheating, where players’ ages are deliberately reduced to fit certain categories, is another widespread issue.

Training methods in some academies are also concerning. Many focus solely on winning rather than teaching children how to understand and enjoy the sport. This approach can negatively impact a child’s mentality, particularly when they lose, as they are treated as if playing elite football. Child football should primarily be about enjoyment and skill development. The practice of reducing ages, which is common across African football, can have long-term detrimental effects on the players’ development.

Despite repeated inquiries, Lamin Jassey, General Secretary of the Gambia Football Federation (GFF), refused to respond to questions and allegations, even after the Ministry of Youth and Sports took over two months to reply.

On 23 July, GAMBIANS AGAINST LOOTED ASSETS (GALA) submitted a petition to the National Sports Council calling for an investigation into alleged corruption within the GFF. The petition highlighted the inadequate support and development opportunities for grassroots football.

GALA petition the GFF

According to GALA, between 2014 and 2024 the GFF received over $11 million from FIFA and CAF to support football infrastructural development, administration and grassroots development across the country. Many of the projects linked to the funds remain incomplete, substandard and completely abandoned.

The Schools Football Association is yet to organise competitions since 2021, which resulted in the collapse of youth football in the country.

For context, if the Ministry of Youth and Sports can allocate D2.3 million to Tijan Jaiteh Football Academy, it is plausible that government funding could cover initiatives offered by Afriskaut. Academies such as Gambinos, Agent Modou Lamin Beyai, Bakary Bojang, Sheriff Jarju, Esohna, Harts FC, Calasbash, Greater Tomorrow, and SEBEC already exist and provide pathways for young talent. From this perspective, Afriskaut’s operations in The Gambia appear questionable, with indications that they may primarily serve personal enrichment rather than the advancement of football in the country.

It is imperative to set clear boundaries and ensure that all stakeholders act responsibly. The Gambia has emerged as a rising force in African football, having participated in the previous two AFCON tournaments. The country possesses abundant talent, and proper nurturing of the next generation is essential. Exploitative practices, such as those allegedly carried out by Afriskaut, risk undermining the potential of young players.

There is also concern that the GFF may present the outcomes of competitions linked to Afriskaut as indicators of grassroots and youth football development to FIFA and CAF. Such a portrayal would be misleading, as these initiatives fall short of proper standards and may be motivated by personal glory.

Regional football associations currently provide limited opportunities for grassroots and youth competitions, mainly focusing on zonal and third-division leagues. This leaves significant gaps in development, which organisations like Badra Pulloq’s initiative are striving to address. Collaborative efforts are necessary to ensure young players have meaningful opportunities to participate and grow.

The Jarra Soma project, operational since 2015, exemplifies neglect and unfulfilled promises. The absence of essential facilities such as seating benches, dressing rooms, and pavilions underscores the lack of commitment to rural football development. GALA

Concerns regarding Afriskaut’s involvement further illustrate the need for accountability. The federation received communication from the organisation, but no agreements were signed. The situation highlights broader issues of corruption within football, which undermine the development of grassroots talent.

Give every talent a chance

Afriskaut’s Clarification on The Alkamba Times Article

We thank The Alkamba Times for sparking a necessary debate on the future of grassroots football in The Gambia. But to have a fair conversation, some realities must be stated clearly.

The fundamental question is: What is the incentive for funding youth tournaments in The Gambia?

If corporate bodies are asked to step in, what should their incentives be? And what tangible benefits should they receive for carrying the financial burden?

In countries like Germany, youth leagues already exist as part of a strong football structure. This makes it easy for data companies like Wyscout to simply plug in, collect statistics, and provide services to clubs. In Africa, the picture is different. The reality is that without consistent youth competitions, there is no data. Without data, there is no visibility for players.

Afriskaut is, at its core, a data company. We built artificial intelligence to collect and analyze performance data on African youth players. But quickly, we faced a barrier: where are the youth leagues for us to collect data from?

This absence pushed us into a role we did not set out to play — that of competition organizer. If we had to fund tournaments ourselves, then naturally we needed a model that allowed sustainability. That is why we structured agreements in ways that have raised concerns around Third Party Ownership (TPO).

Our intent was not to control players, but to ensure that the heavy cost of organizing tournaments could be balanced against future returns.

Now, with this article styled to misrepresent us, Afriskaut is being forced to reconsider. If we are criticized for stepping in to fill a gap that no one else has been willing to fill, then the simple reality is that we may have no choice but to stop funding these tournaments altogether.

Our business model is built on data, not competition organization. If tournaments cannot be sustainably funded, then the data on Gambian youth football risks disappearing altogether.

Afriskaut should be commended for refusing to let young players go unseen. Instead of waiting for structures to appear, we built them — at our own cost — so that players could have a stage and clubs could have information.

So we leave readers with these crossroads:

- If corporate bodies should not fund youth tournaments, then who will?

- If corporate bodies do fund, how should their incentives be structured to ensure sustainability and fairness?

- And finally, when a data company is forced into competition organizing just to ensure the very existence of youth football data — should they be condemned, or supported?

Afriskaut remains committed to transparency and dialogue. But unless all stakeholders take ownership of grassroots football, the risk is clear: the very competitions that give young Gambians a chance to be seen may cease to exist.

Nnamdi Emefo