By Ebrima Mbaye

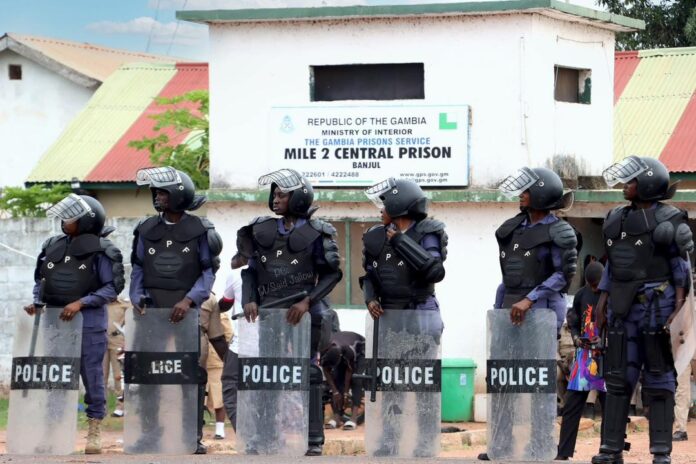

When Lamin Ceesay walked out of Mile Two Central Prison after a four-year sentence, he carried more than his release papers. “My body left, but my mind is still locked behind those rusted gates,” he said, his voice trembling with the weight of trauma. For Ceesay and countless others, Mile 2 is not just a prison—it’s a crucible of suffering that reveals the dark underbelly of The Gambia’s justice system.

Nestled on the outskirts of Banjul, Mile Two stands as a decaying monument to the country’s colonial and dictatorial past. Built in the early 20th century to house a few hundred inmates, the prison now buckles under severe overcrowding, crumbling infrastructure, and conditions that strip inmates of dignity. Its peeling walls and leaking ceilings tell a story of neglect, while the voices of former prisoners paint a vivid picture of despair.

A Prison of Squalor and Silence

Mile Two’s physical state mirrors the neglect within. Former inmates describe cells so cramped that up to 25 men share spaces meant for far fewer. “There were days we slept sitting up. There was no space,” said one ex-convict, who was freed after paying fines following a two-year sentence. During the rainy season, cells become swamps of filth, with floors slick from leaks and poor sanitation.

Food is another ordeal. Meals—often thin porridge in the morning and barely edible rice at night—leave inmates perpetually hungry. “I lost my body size in four months. My skin was affected. I thought I would die,” said another former prisoner, who spoke anonymously. Medical care is scarce, with the prison’s clinic lacking basic supplies. Inmates with mental health issues fare worse, often confined to solitary cells rather than treated. Detainees from the recent PURA protest reported that a prison doctor admitted that medications must be purchased externally by families.

A System That Punishes, Not Reforms

The Gambia’s prison system offers little hope for rehabilitation. “When you go in, they treat you like an animal. And when you come out, society still sees you as one,” Ceesay said. Without meaningful programs, inmates leave unprepared for life outside, facing stigma and unemployment. The absence of skills training or psychological support perpetuates cycles of crime and recidivism.

Recent detainees, including journalist Yusuf Taylor, have brought renewed attention to these issues. Arrested during the August 2025 PURA protests, Taylor spent two nights in Mile Two’s remand wing. “It was a brutal awakening,” he said. “The cell wasn’t big, but 26 people were crammed inside. The food was so unhygienic, we threw it away most days.” Taylor, alongside activists Ebrima Jallow (The Ghetto Pen) and Ali Cham (Killer Ace), has vowed to advocate for reform. “The system is broken beyond words,” Jallow said, while Cham called for an overhaul of “draconian prison laws” that prioritize punishment over redemption.

Overcrowding and Systemic Failures

The National Assembly’s Human Rights and Constitutional Matters Committee, led by Hon. Madi Ceesay, recently toured Mile Two and described conditions as “pathetic.” The prison, designed for 400 inmates, now holds 733—432 convicted and 255 on remand. Nearly 75% of inmates are youths aged 20 to 35, a statistic Hon. Ceesay called “alarming.” He noted cells holding 27 men where only 10 to 20 should be, with no proper segregation for those with tuberculosis or psychiatric conditions.

“The medical unit lacks essential medicines and equipment,” Hon. Ceesay said. “We’re wasting a vital part of our future by locking away young people without programs to prepare them for reintegration.” Defense lawyer Sagarr Jahateh echoed this, branding Mile Two a “champion of human rights violations” due to overcrowding, unfit conditions, and unlawful remand practices. She and organizations like Amnesty International have long urged The Gambia to align its prison system with international standards.

Official Defenses Amid Criticism

Superintendent Luke Jatta, Public Relations Officer for The Gambia Prisons Service, defended the institution’s efforts. “No one is detained without due process,” he told The Alkamba Times, contrasting current practices with the Jammeh era’s arbitrary detentions. Jatta highlighted health screenings for new inmates, a degree-holding infirmary head, and ambulances at Mile 2, Jeshwang, and Janjangbureh. He also highlighted ongoing renovations and vocational programs, noting that between 2023 and 2024, over 290 inmates and officers graduated from training in ICT, solar installation, and other skills, with a reoffending rate of less than 3%.

Yet, a prison officer speaking anonymously painted a bleaker picture: “The system is broken, and we can’t fix it from inside.” Promises of reform, including 2019 pledges for renovations and expanded programs, have yielded little visible change, leaving Mile 2 a symbol of systemic failure.

A Call for Change

As The Gambia navigates its post-Jammeh democratic transition, Mile Two remains a stark reminder of unfinished work. “There’s nothing corrective about our correctional system,” Ceesay said, walking away from the prison’s shadow. “If you want to know the true face of justice in this country, don’t go to the courts. Go to Mile 2.”

For human rights advocates, Mile Two is more than an outdated facility—it’s a living violation of dignity. As activists like The Ghetto Pen and Killer Ace amplify inmates’ stories, the nation faces a choice: continue neglecting its prisoners or reform a system that imprisons not just bodies, but potential. The walls of Mile Two may whisper pain, but the cries for justice are growing louder.